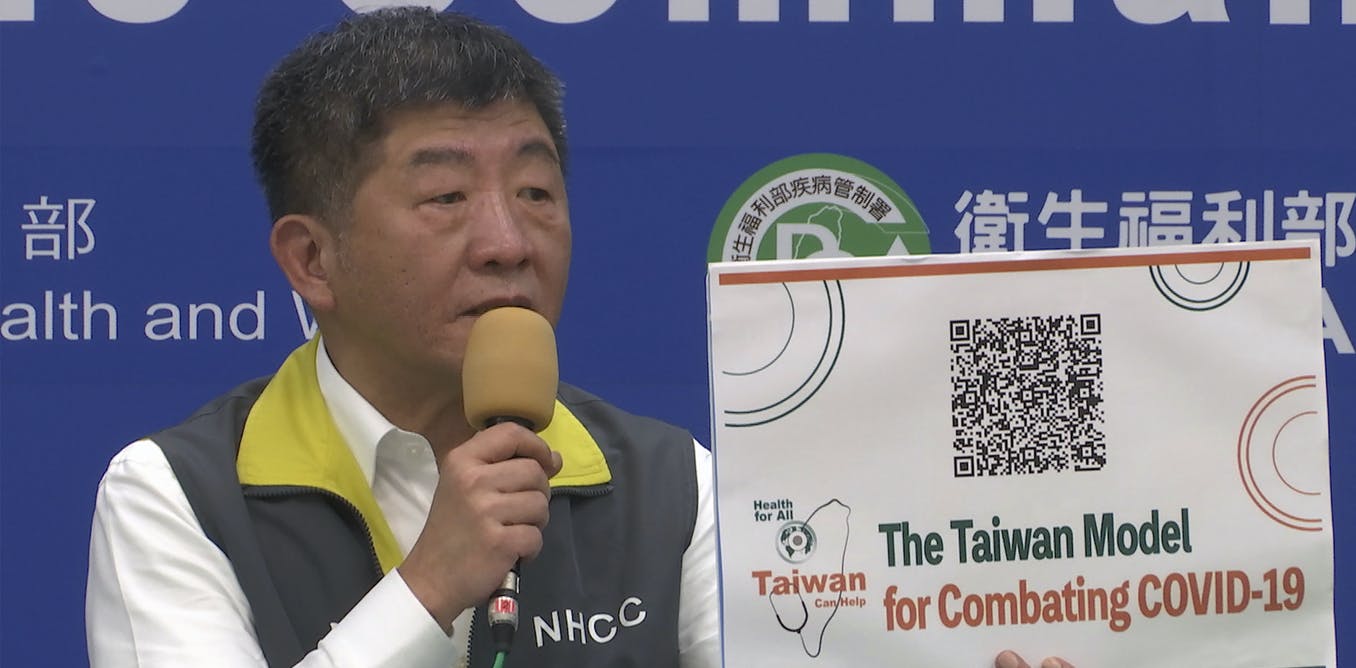

Hacking the pandemic: how Taiwan’s digital democracy holds COVID-19 at bay

Taiwan’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been among the world’s best. With a population almost the size of Australia’s, the island nation has reported only 496 confirmed cases of the disease and no locally acquired infections for months.

The unlikely heroes of Taiwan’s success are “civic tech hacktivists”: coders and activists who the country’s celebrity digital minister Audrey Tang describes as the “nobodies” who “hack democracy”.

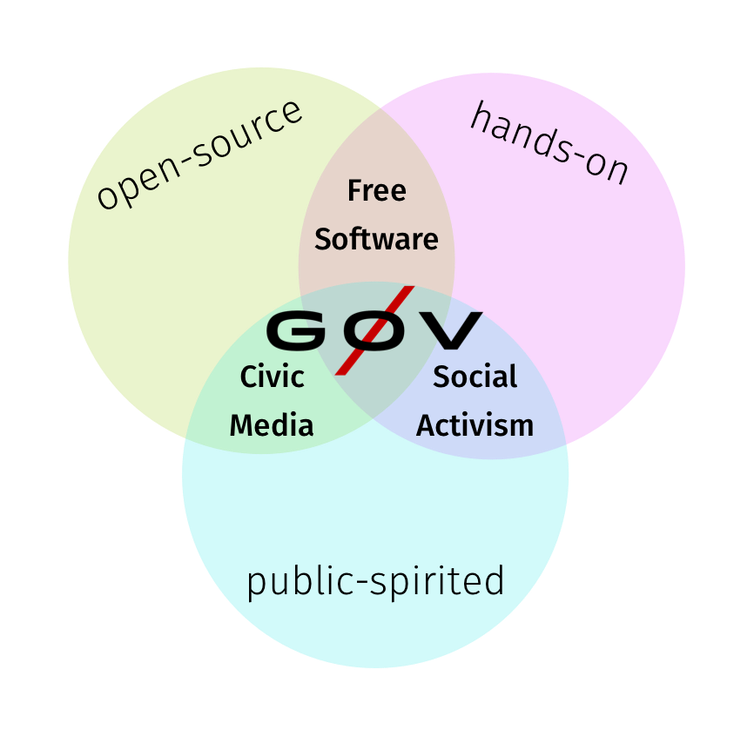

What began with the hackers of the “open source, open government” movement g0v and student protesters has grown into an experiment in radical democracy that is yielding astonishing results.

Read more:

Another day, another hotel quarantine fail. So what can Australia learn from other countries?

‘Fast, fair and fun’

While the notion of “digital democracy” is as old as the internet, few countries have really tried to find out how to practice democracy in digital spheres. In Taiwan, however, there is a strong collective narrative of digital democracy, and government and civil society work together in online spaces to build public trust.

The growth of civic hacking in Taiwan has its roots in the so-called Sunflower Movement, a stream of protests in 2014 against a trade agreement with China.

The pillars of Taiwan’s approach to digital democracy are “fast, fair and fun”.

Taiwan was among the first countries in the world to detect and respond to the virus, thanks to crowd-sourced, collective intelligence through online bulletin boards. Warnings of the virus were first noted in December 31 2019, when a senior health official spotted a heavily “up-voted” post on the PTT bulletin board.

Before long, civic tech hackers were working on open data projects for citizens to interact with live maps, distributed ledger technology and chat bots to find the nearest pharmacy to claim free masks, with stock levels updated in real time to stop panic buying. Audrey Tang dubbed this rapid, iterative, bottom-up process – as opposed to a top-down government-led distribution system – “reverse procurement”.

A “humour over rumour” strategy has also been very successful to combat misinformation, fake news and disinformation. Taiwan is engineering memes to spread public awareness of positive behaviours through the virality of social media algorithms.

Government departments are responsible for addressing disinformation by providing a “memetic” response according to the “2-2-2”: a response in 20 minutes, in 200 words or less, with 2 images.

Alongside dog memes and pink face masks, one of the most successful is a rapid response to halt runs on toilet paper. This featured a cartoon video of Taiwan Premier Su Tseng-chang shaking his backside with a caption saying “We only have one pair of buttocks”.

Meme of television presenters obvserving Premier Su Tseng-chang’s figure with the slogan ‘We only have one pair of buttocks’.

How hacktivists reached the halls of power

How has the mindset and culture of hacktivism been cultivated to motivate civic hackers to participate in Taiwan’s digital democracy?

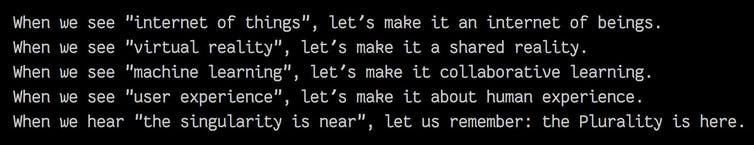

First, a figurehead and a manifesto. Audrey Tang is the figurehead, and her manifesto On Utopia for Public Action espouses post-party politics, free speech and deliberation, all enabled through thoughtful and experimental application of digital infrastructure.

Audrey Tang’s ‘prayer’ at the Open Source, Open Society 2016 conference.

YouTube

Second, a suite of smart digital tools enable discussion, survey and online “telepresence”. These include the vTaiwan and the Join platforms for public policy participation.

Read more:

Digital democracy lets you write your own laws

Third, inviting participation, listening to community voices, and taking action as a result. Taiwan’s culture of civic participation follows the model of open source software communities. This means working from the bottom up, sharing information, improving on the work of others, mutual benefit and participatory collective action.

g0v.asia is a ‘decentralized civic tech community from Taiwan’.

Underlying these initiatives and digital infrastructures, is two-way trust. In the words of Yun Chen, a member of the “decentralized civic tech community” g0v:

The first key is trust … it was the trust that made government officers take open data as performance instead of troubles, which led government to initiate open data and be willing to accept tech assistance from civic tech communities.

Despite low overall trust in government and leadership in Taiwan, recent polling suggests 91% of citizens are satisfied with the Central Epidemic Command Centre. Tang has said “the government needs to fully trust the citizens”, and that this trust is reciprocated.

A small experiment

With all of this enthusiasm, I wanted to try participating in digital democracy myself. I had heard Tang quote some statistics on increased public trust in several interviews, but I couldn’t find the source. At the suggestion of my Taiwanese compatriot Chih Cheng Liang, I simply asked Tang for the source on Twitter.

Tang’s response was extremely impressive: in less than 5 minutes, she replied with a link to the relevant Taiwanese poll.

A radical experiment

In many countries, policy makers don’t fully understand the technical and governance dynamics of the digital realm. In Taiwan, we are seeing what can happen when they do: bringing “hacker” tools and methods into the institutions of government to increase public participation in democracy.

It’s a vast change. Digital infrastructures are inherently political, or spheres for political engagement. They emerge out of the interaction between technology and society, and are influenced and constrained by human agents.

Radical democracy is essentially radical. Tang also sits on the board of of American economist Glen Weyl’s Radical Xchange initiative, which aims at “uprooting capitalism and democracy for a just society”.

There is now talk of trying out the collective decision making system known as “quadratic voting”, and other experimental crowd-sourcing mechanisms that have surfaced from the Ethereum blockchain community.

Other countries are free to pick up both lessons and digital innovations from Taiwan’s innovations. Many tools and models have been made available on an open-source basis at Taiwancanhelp.us.

An image from g0v.tw illustrates the movement’s goal of radical democracy.

Read more:

What coronavirus success of Taiwan and Iceland has in common

Kelsie Nabben does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.