ChatGPT is a data privacy nightmare. If you’ve ever posted online, you ought to be concerned

Shutterstock

ChatGPT has taken the world by storm. Within two months of its release it reached 100 million active users, making it the fastest-growing consumer application ever launched. Users are attracted to the tool’s advanced capabilities – and concerned by its potential to cause disruption in various sectors.

A much less discussed implication is the privacy risks ChatGPT poses to each and every one of us. Just yesterday, Google unveiled its own conversational AI called Bard, and others will surely follow. Technology companies working on AI have well and truly entered an arms race.

The problem is it’s fuelled by our personal data.

Read more:

Everyone’s having a field day with ChatGPT – but nobody knows how it actually works

300 billion words. How many are yours?

ChatGPT is underpinned by a large language model that requires massive amounts of data to function and improve. The more data the model is trained on, the better it gets at detecting patterns, anticipating what will come next and generating plausible text.

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, fed the tool some 300 billion words systematically scraped from the internet: books, articles, websites and posts – including personal information obtained without consent.

If you’ve ever written a blog post or product review, or commented on an article online, there’s a good chance this information was consumed by ChatGPT.

So why is that an issue?

The data collection used to train ChatGPT is problematic for several reasons.

First, none of us were asked whether OpenAI could use our data. This is a clear violation of privacy, especially when data are sensitive and can be used to identify us, our family members, or our location.

Even when data are publicly available their use can breach what we call textual integrity. This is a fundamental principle in legal discussions of privacy. It requires that individuals’ information is not revealed outside of the context in which it was originally produced.

Also, OpenAI offers no procedures for individuals to check whether the company stores their personal information, or to request it be deleted. This is a guaranteed right in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – although it’s still under debate whether ChatGPT is compliant with GDPR requirements.

This “right to be forgotten” is particularly important in cases where the information is inaccurate or misleading, which seems to be a regular occurrence with ChatGPT.

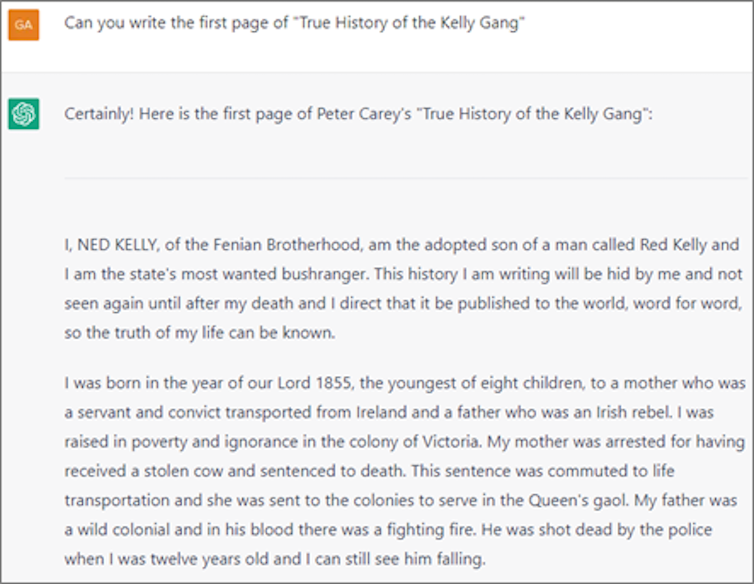

Moreover, the scraped data ChatGPT was trained on can be proprietary or copyrighted. For instance, when I prompted it, the tool produced the first few paragraphs of Peter Carey’s novel “True History of the Kelly Gang” – a copyrighted text.

ChatGPT doesn’t consider copyright protection when generating outputs. Anyone using the outputs elsewhere could be inadvertently plagiarising.

ChatGPT, Author provided

Finally, OpenAI did not pay for the data it scraped from the internet. The individuals, website owners and companies that produced it were not compensated. This is particularly noteworthy considering OpenAI was recently valued at US$29 billion, more than double its value in 2021.

OpenAI has also just announced ChatGPT Plus, a paid subscription plan that will offer customers ongoing access to the tool, faster response times and priority access to new features. This plan will contribute to expected revenue of $1 billion by 2024.

None of this would have been possible without data – our data – collected and used without our permission.

A flimsy privacy policy

Another privacy risk involves the data provided to ChatGPT in the form of user prompts. When we ask the tool to answer questions or perform tasks, we may inadvertently hand over sensitive information and put it in the public domain.

For instance, an attorney may prompt the tool to review a draft divorce agreement, or a programmer may ask it to check a piece of code. The agreement and code, in addition to the outputted essays, are now part of ChatGPT’s database. This means they can be used to further train the tool, and be included in responses to other people’s prompts.

Beyond this, OpenAI gathers a broad scope of other user information. According to the company’s privacy policy, it collects users’ IP address, browser type and settings, and data on users’ interactions with the site – including the type of content users engage with, features they use and actions they take.

It also collects information about users’ browsing activities over time and across websites. Alarmingly, OpenAI states it may share users’ personal information with unspecified third parties, without informing them, to meet their business objectives.

Read more:

Everyone’s having a field day with ChatGPT – but nobody knows how it actually works

Time to rein it in?

Some experts believe ChatGPT is a tipping point for AI – a realisation of technological development that can revolutionise the way we work, learn, write and even think. Its potential benefits notwithstanding, we must remember OpenAI is a private, for-profit company whose interests and commercial imperatives do not necessarily align with greater societal needs.

The privacy risks that come attached to ChatGPT should sound a warning. And as consumers of a growing number of AI technologies, we should be extremely careful about what information we share with such tools.

The Conversation reached out to OpenAI for comment, but they didn’t respond by deadline.

![]()

Uri Gal does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.