Generative AI: 5 essential reads about the new era of creativity, job anxiety, misinformation, bias and plagiarism

What does generative AI mean for the human need to create, work and seek the truth? Krerksak Woraphoomi/iStock via Getty Images

The light and dark sides of AI have been in the public spotlight for many years. Think facial recognition, algorithms making loan and sentencing recommendations, and medical image analysis. But the impressive – and sometimes scary – capabilities of ChatGPT, DALL-E 2 and other conversational and image-conjuring artificial intelligence programs feel like a turning point.

The key change has been the emergence within the last year of powerful generative AI, software that not only learns from vast amounts of data but also produces things – convincingly written documents, engaging conversation, photorealistic images and clones of celebrity voices.

Generative AI has been around for nearly a decade, as long-standing worries about deepfake videos can attest. Now, though, the AI models have become so large and have digested such vast swaths of the internet that people have become unsure of what AI means for the future of knowledge work, the nature of creativity and the origins and truthfulness of content on the internet.

Here are five articles from our archives the take the measure of this new generation of artificial intelligence.

1. Generative AI and work

A panel of five AI experts discussed the implications of generative AI for artists and knowledge workers. It’s not simply a matter of whether the technology will replace you or make you more productive.

University of Tennessee computer scientist Lynne Parker wrote that while there are significant benefits to generative AI, like making creativity and knowledge work more accessible, the new tools also have downsides. Specifically, they could lead to an erosion of skills like writing, and they raise issues of intellectual property protections given that the models are trained on human creations.

University of Colorado Boulder computer scientist Daniel Acuña has found the tools to be useful in his own creative endeavors but is concerned about inaccuracy, bias and plagiarism.

University of Michigan computer scientist Kentaro Toyama wrote that human skill is likely to become costly and extraneous in some fields. “If history is any guide, it’s almost certain that advances in AI will cause more jobs to vanish, that creative-class people with human-only skills will become richer but fewer in number, and that those who own creative technology will become the new mega-rich.”

Florida International University computer scientist Mark Finlayson wrote that some jobs are likely to disappear, but that new skills in working with these AI tools are likely to become valued. By analogy, he noted that the rise of word processing software largely eliminated the need for typists but allowed nearly anyone with access to a computer to produce typeset documents and led to a new class of skills to list on a resume.

University of Colorado Anschutz biomedical informatics researcher Casey Greene wrote that just as Google led people to develop skills in finding information on the internet, AI language models will lead people to develop skills to get the best output from the tools. “As with many technological advances, how people interact with the world will change in the era of widely accessible AI models. The question is whether society will use this moment to advance equity or exacerbate disparities.”

Read more:

AI and the future of work: 5 experts on what ChatGPT, DALL-E and other AI tools mean for artists and knowledge workers

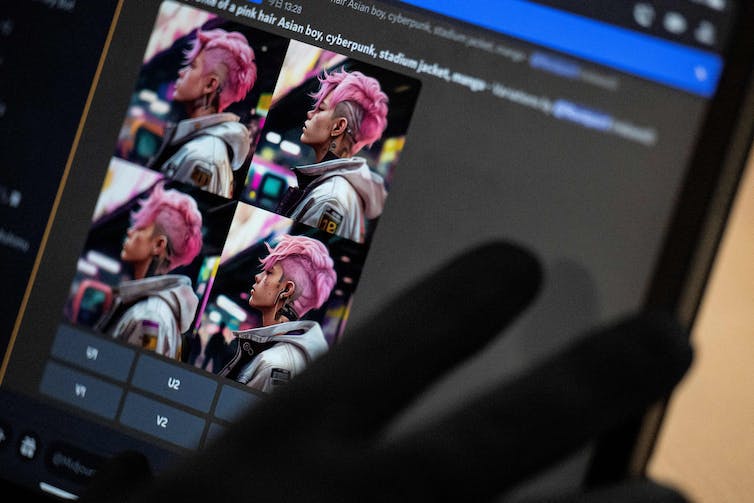

2. Conjuring images from words

Generative AI can seem like magic. It’s hard to imagine how image-generating AIs can take a few words of text and produce an image that matches the words.

A few keywords – pink hair, Asian boy, cyberpunk, stadium jacket, Manga – yield striking and believable images of a person who never existed.

Richard A. Brooks/AFP via Getty Images

Hany Farid, a University of California, Berkeley computer scientist who specializes in image forensics, explained the process. The software is trained on a massive set of images, each of which includes a short text description.

“The model progressively corrupts each image until only visual noise remains, and then trains a neural network to reverse this corruption. Repeating this process hundreds of millions of times, the model learns how to convert pure noise into a coherent image from any caption,” he wrote.

Read more:

Text-to-image AI: powerful, easy-to-use technology for making art – and fakes

3. Marking the machine

Many of the images produced by generative AI are difficult to distinguish from photographs, and AI-generated video is rapidly improving. This raises the stakes for combating fraud and misinformation. Fake videos of corporate executives could be used to manipulate stock prices, and fake videos of political leaders could be used to spread dangerous misinformation.

Farid explained how it’s possible to produce AI-generated photos and video that contain watermarks verifying that they are synthetic. The trick is to produce digital watermarks that can’t be altered or removed. “These watermarks can be baked into the generative AI systems by watermarking all the training data, after which the generated content will contain the same watermark,” he wrote.

Read more:

Watermarking ChatGPT, DALL-E and other generative AIs could help protect against fraud and misinformation

4. Flood of ideas

For all the legitimate concern about the downsides of generative AI, the tools are proving to be useful for some artists, designers and writers. People in creative fields can use the image generators to quickly sketch out ideas, including unexpected off-the-wall material.

AI as an idea generator for designers.

Rochester Institute of Technology industrial designer and professor Juan Noguera and his students use tools like DALL-E or Midjourney to produce thousands of images from abstract ideas – a sort of sketchbook on steroids.

“Enter any sentence – no matter how crazy – and you’ll receive a set of unique images generated just for you. Want to design a teapot? Here, have 1,000 of them,” he wrote. “While only a small subset of them may be usable as a teapot, they provide a seed of inspiration that the designer can nurture and refine into a finished product.”

Read more:

DALL-E 2 and Midjourney can be a boon for industrial designers

5. Shortchanging the creative process

However, using AI to produce finished artworks is another matter, according to Nir Eisikovits and Alec Stubbs, philosophers at the Applied Ethics Center at University of Massachusetts Boston. They note that the process of making art is more than just coming up with ideas.

The hands-on process of producing something, iterating the process and making refinements – often in the moment in response to audience reactions – are indispensable aspects of creating art, they wrote.

“It is the work of making something real and working through its details that carries value, not simply that moment of imagining it,” they wrote. “Artistic works are lauded not merely for the finished product, but for the struggle, the playful interaction and the skillful engagement with the artistic task, all of which carry the artist from the moment of inception to the end result.”

Read more:

ChatGPT, DALL-E 2 and the collapse of the creative process

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

![]()