Your AI therapist is not your therapist: The dangers of relying on AI mental health chatbots

The design and marketing of mental health chatbots may result in users' misconceptions about their therapeutic value. (Shutterstock)

With current physical and financial barriers to accessing care, people with mental health conditions may turn to artificial intelligence (AI)-powered chatbots for mental health relief or aid. Although they have not been approved as medical devices by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or Health Canada, the appeal to use such chatbots may come from their 24/7 availability, personalized support and marketing of cognitive behavioural therapy.

However, users may overestimate the therapeutic benefits and underestimate the limitations of using such technologies, further deteriorating their mental health. Such a phenomenon can be classified as a therapeutic misconception where users may infer the chatbot’s purpose is to provide them with real therapeutic care.

With AI chatbots, therapeutic misconceptions can occur in four ways, through two main streams: the company’s practices and the design of the AI technology itself.

Company practices: Meet your AI self-help expert

First, inaccurate marketing of mental health chatbots by companies that label them as “mental health support” tools that incorporate “cognitive behavioural therapy” can be very misleading as it implies that such chatbots can perform psychotherapy.

Not only do such chatbots lack the skill, training and experience of human therapists, but labelling them as being able to provide a “different way to treat” mental illness insinuates that such chatbots can be used as alternative ways to seek therapy.

This sort of marketing tactic can be very exploitative of users’ trust in the health-care system, especially when they are marketed as being in “close collaboration with therapists.” Such marketing tactics can lead users to disclose very personal and private health information without fully comprehending who owns and has access to their data.

The second type of therapeutic misconception is when a user forms a digital therapeutic alliance with a chatbot. With a human therapist, it’s beneficial to form a strong therapeutic alliance where both the patient and therapist collaborate and agree on desired goals that can be achieved through tasks, and form a bond built on trust and empathy.

Since a chatbot cannot develop the same therapeutic relationship as users can with a human therapist, a digital therapeutic alliance can form, where a user perceives an alliance with the chatbot, even though the chatbot can’t actually form one.

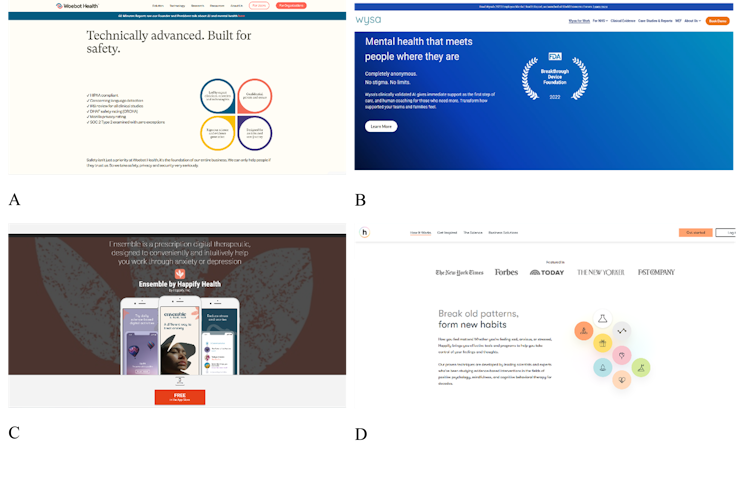

Examples of how mental health apps are presented: (A) Screenshot taken from Woebot Health website. (B) Screenshot taken from Wysa website. (C) Advertisement of Anna by Happify Health. (D) Screenshot taken from Happify Health website.

(Zoha Khawaja)

A great deal of effort has been made to gain user trust and fortify digital therapeutic alliance with chatbots, including giving chatbots humanistic qualities to resemble and mimic conversations with actual therapists and advertising them as “anonymous” 24/7 companions that can replicate aspects of therapy.

Such an alliance may lead users to inadvertently expect the same patient-provider confidentiality and protection of privacy as they would with their health-care providers. Unfortunately, the more deceptive the chatbot is, the more effective the digital therapeutic alliance will be.

Technological design: Is your chatbot trained to help you?

The third therapeutic misconception occurs when users have limited knowledge about possible biases in the AI’s algorithm. Often marginalized people are left out of the design and development stages of such technologies which may lead to them receiving biased and inappropriate responses.

Read more:

Artificial intelligence can discriminate on the basis of race and gender, and also age

When such chatbots are unable to recognize risky behaviour or provide culturally and linguistically relevant mental health resources, this could worsen the mental health conditions of vulnerable populations who not only face stigma and discrimination, but also lack access to care. A therapeutic misconception occurs when users may expect the chatbot to benefit them therapeutically but are provided with harmful advice.

Lastly, a therapeutic misconception can occur when mental health chatbots are unable to advocate for and foster relational autonomy, a concept that emphasizes that an individual’s autonomy is shaped by their relationships and social context. It is then the responsibility of the therapist to help recover a patient’s autonomy by supporting and motivating them to actively engage in therapy.

AI-chatbots provide a paradox in which they are available 24/7 and promise to improve self-sufficiency in managing one’s mental health. This can not only make help-seeking behaviours extremely isolating and individualized but also creates a therapeutic misconception where individuals believe they are autonomously taking a positive step towards amending their mental health.

A false sense of well-being is created where a person’s social and cultural context and the inaccessibility of care are not considered as contributing factors to their mental health. This false expectation is further emphasized when chatbots are incorrectly advertised as “relational agents” that can “create a bond with people…comparable to that achieved by human therapists.”

Measures to avoid the risk of therapeutic misconception

Not all hope is lost with such chatbots, as some proactive steps can be taken to reduce the likelihood of therapeutic misconceptions.

Through honest marketing and regular reminders, users can be kept aware of the chatbot’s limited therapeutic capabilities and be encouraged to seek more traditional forms of therapy. In fact, a therapist should be made available for those who’d like to opt-out of using such chatbots. Users would also benefit from transparency on how their information is collected, stored and used.

Active involvement of patients during the design and development stages of such chatbots should also be considered, as well as engagement with multiple experts on ethical guidelines that can govern and regulate such technologies to ensure better safeguards for users.

![]()

Zoha Khawaja receives funding from AI4PH-HRTP and SPARK Good AI Lab.

Jean-Christophe Bélisle-Pipon receives funding from the US NIH Common Fund (OT2OD032720 & OT2OD032742) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SFU/SSHRC Small Explore Research Grant).