Cyberattacks to critical infrastructure threaten our safety and well-being

Our critical infrastructures are growing increasingly complex as the number of devices and connections in these systems continues to grow. (Shutterstock)

What would happen if you could no longer use the technological systems that you rely on every day? I’m not talking about your smart phone or laptop computer, but all those systems many of us often take for granted and don’t think about.

What if you could not turn on the lights or power your refrigerator? What if you could not get through to emergency services when you dial 911? What if you could not access your bank account, get safe drinking water or even flush your toilet?

According to Canada’s National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure, critical infrastructure refers to the processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of the public and the effective functioning of government.

Disruptions to these kinds of systems, especially those caused by cyberattacks, can have devastating consequences. That’s why these systems are called critical infrastructure.

A string of attacks

Over the past six months, the fragility of critical infrastructure has been given plenty of attention. This has been driven by a string of notable cyberattacks on several critical infrastructure sectors.

It was revealed that in late March 2021, CNA Financial Corp., one of the largest insurance companies in the United States was victim to a ransomware attack. As a result, the company faced disruptions of their systems and networks.

In May 2021, a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline halted plant operations for six days. The attack led to a fuel crisis and increased prices in the eastern U.S.

MSNBC looks at the cybersecurity concerns raised by the attack on Colonial Pipeline.

Weeks later, in June 2021, a ransomware attack hit JBS USA Holdings, Inc., one of the world’s largest meat producers. This attack brought about supply chain turmoil in Canada, the U.S. and Australia.

Also in June 2021, the Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority was victim of a ransomware attack that disrupted ferry services and caused service delays.

Fragile infrastructures

On Oct. 14, 2021, hot on the heels of cyberattacks targeting the financial, gas, food and transportation sectors, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency released Alert AA21-287.

The alert turns attention to the fragility of yet another critical infrastructure sector. It warns of “ongoing malicious cyberactivity” targeting water and wastewater facilities. These activities include exploits of internet-connected services and outdated operating systems and software, as well as spear phishing and ransomware attacks – something we have seen a lot in recent cyberattacks.

According to the alert, these cyberthreats could impact the ability of water and wastewater facilities to “provide clean, potable water to, and effectively manage the wastewater of, their communities.”

Vulnerability factors

The need for combating cyberthreats to critical infrastructure is well recognized. However, the infrastructure today is far from secure. This is due to a many interrelated factors that create a perfect storm of exposures.

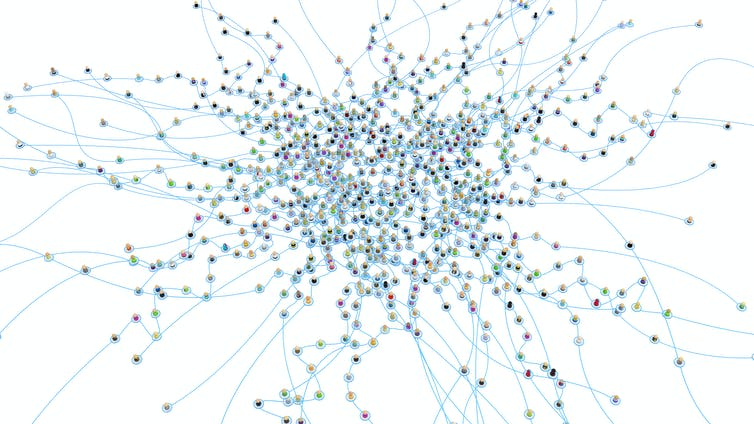

First, many of our most critical systems are extremely complex. This complexity is rapidly increasing as the number of devices and connections in these systems continues to grow.

Second, many of these systems involve a mix of insecure, outdated legacy systems and new technologies. These new technologies promise features like advanced analytics and automation. However, they are sometimes connected and used in insecure ways that the original designers of the legacy systems could not have imagined.

Taken together, these factors mean that these systems are too complex to be completely understood by a person, a team of people or even a computer model. This makes it very difficult to identify weak spots that if exploited — accidentally or intentionally — could lead to system failures.

Analyzing real-world complexities

In the Cyber Security Evaluation and Assurance (CyberSEA) Research Lab at Carleton University, we are developing solutions to address the fragility of critical infrastructure. The goal is to improve security and resilience of these important systems.

The complexities of critical infrastructure can lead to unexpected or unplanned interactions among system components, known as implicit interactions.

Exploitation of implicit interactions has the potential to impact the safety, security and reliability of a system and its operations. For example, implicit interactions can enable system components to interact in unintended — and often undesirable — ways. This leads to unpredictable system behaviours that can allow attackers to damage or disrupt the system and its operations.

Infrastructure systems become increasingly complex as new connections and devices are added to critical infrastructure with updates in technologies.

(Shutterstock)

We recently conducted a cybersecurity analysis at CyberSEA on a real-world municipal wastewater treatment system, where we identified and measured characteristics of implicit interactions in the system. This was part of our ongoing research, conducted in partnership with the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Institute at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Our analysis found a significant proportion of implicit interactions present in the system, and approximately 28 per cent of these identified vulnerabilities showed signs of being ripe for attackers to exploit and cause damage or disruption in the system.

A glimmer of hope

Our study showed that implicit interactions exist in real-world critical infrastructure systems. Feedback from the operators of the wastewater system in our case study stated that our approaches and tools are useful for identifying potential security issues and informing mitigation efforts when designing critical systems.

This may be a glimmer of hope in the fight against cyberthreats to critical infrastructure. Continued development of rigorous and practical approaches to address increasingly critical issues in designing, implementing, evaluating and assuring the safe, secure and reliable operation of these systems is needed.

A more robust infrastructure will lead to fewer threats to our security and access to services, ensuring our well-being and the effective functioning of our governments and society.

Jason Jaskolka receives funding from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Grant 2015-ST-061-CIRC01 and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant RGPIN-2019-06306.