Urban owls are losing their homes. So we’re 3D printing them new ones

Nick Bradsworth, Author provided

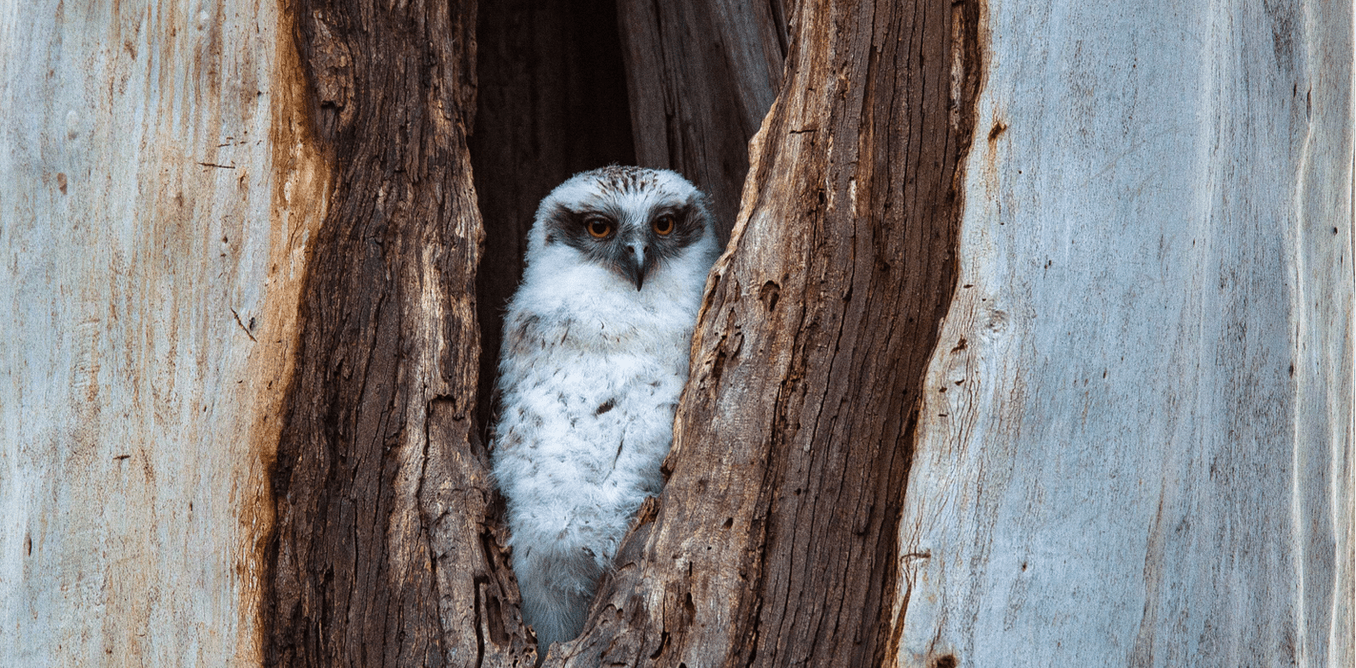

Native to southeastern Australia, the powerful owl (Ninox strenua) is threatened and facing the prospect of homelessness.

These birds don’t make nests – they use large hollows in old, tall trees. But humans have been removing such trees in the bush and in cities, despite their ecological value.

Read more:

To save these threatened seahorses, we built them 5-star underwater hotels

Owls are lured into cities by abundant prey, with each bird capturing hundreds of possums per year. But with nowhere to nest, they struggle to breed and their population is at risk of declining even further.

Existing artificial nest designs include nesting boxes and carved logs.

Author provided

Conservationists tried to solve this problem by installing nesting boxes, but to no avail. A 2011 study in Victoria showed a pair of owls once used such a box, but only one of their two chicks survived. This is the only recorded instance of powerful-owl breeding in an artificial structure.

So as a team of designers and ecologists we’re finding a way to make artificial nests in urban areas more appealing to powerful owls. Surprisingly, the answer lies in termite mounds, augmented reality and 3D printing.

Bring in the designers

Nesting boxes aren’t very successful for many species. For example, many boxes installed along expanded highways fail to attract animals such as the squirrel glider, the superb parrot and the brown treecreeper. They also tend to disintegrate and become unusable after only a few years.

Read more:

The plan to protect wildlife displaced by the Hume Highway has failed

What’s more, flaws in their design can lead to overheating, death from toxic fumes such as marine-plywood vapours, or babies unable to grow.

Designers and architects often use computer modelling to mimic nature in building designs, such as Beijing’s bird’s nest stadium.

But to use these skills to help wildlife, we need to understand what they want in a home. And for powerful owls, this means thinking outside the box.

What powerful owls need

At a minimum, owl nests must provide enough space to support a mother and two chicks, shelter the inhabitants from rain and heat, and have rough internal surfaces for scratching and climbing.

Traditionally, owls would find all such comforts in large, old, hollow-bearing trees, such as swamp or manna gums at least 150 years old. But a picture from Sydney photographer Ofer Levy, which showed an owl nesting in a tree-bound termite mound, made us realise there was another way.

Owls have been observed using termite mounds in trees for nesting.

Blantyre, Author provided

Termite mounds in trees are oddly shaped, but they meet all necessary characteristics for successful breeding. This precedent suggests younger, healthier and more common trees can become potential nesting sites.

A high-tech home

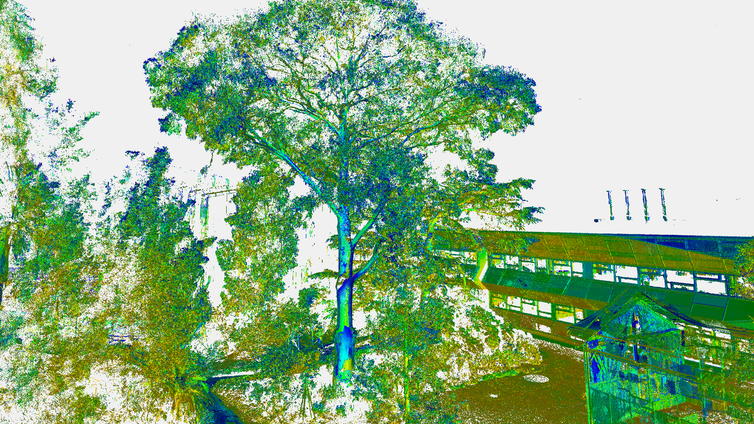

To design and create each termite-inspired nest, we first use lasers to model the shape of the target tree. A computer algorithm generates the structure fitting the owls’ requirements. Then, we divide the structure into interlocking blocks that can be conveniently manufactured.

Trees and their surroundings can be scanned by lasers for precise fitting.

Author provided

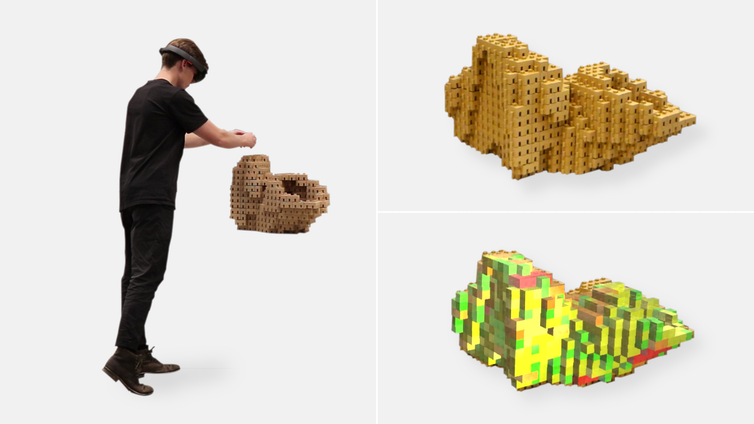

To assemble the nests, we use augmented-reality headsets, overlaying images of digital models onto physical objects. It sounds like science-fiction, but holographic construction with augmented reality has become an efficient way to create new structures.

So far, we’ve used 3D-printed wood to build one nest at the University of Melbourne’s System Garden. Two more nests made from hemp concrete are on the trees in the city of Knox, near the Dandenong Ranges. And we’re exploring other materials such as earth or fungus.

These materials can be moulded to a unique fit, and as they’re lightweight, we can easily fix them onto trees.

With augmented reality, it is easy to know where to place each block. Right: Views from the augmented reality headset.

Author provided

So is it working?

We are still collecting and analysing the data, but early results are promising. Our nests have important advantages over both traditional nesting boxes and carved logs.

This is, in part, because our artificial nests maintain more stable internal temperatures than nesting boxes and are considerably easier to make and install than carved logs. In other words, our designs already look like a good alternative.

Read more:

B&Bs for birds and bees: transform your garden or balcony into a wildlife haven

And while it’s too early to say if they’ll attract owls, our nests have already been visited or occupied by other animals, such as rainbow lorikeets.

Future homes for animal clients

Imagine an ecologist, a park manager or even a local resident who wants to boost local biodiversity. In the not-too-distant future, they might select a target species and a suitable tree from an online database. An algorithm could customise their choice of an artificial-nest design to fit the target tree. Remote machines would manufacture the parts and the end user would put the structure together.

Nests from 3D printed wood are easy to install.

Author provided

Such workflows are already being used in a variety of fields, such as the custom jewellery production and the preparation of dental crowns. It allows informed and automated reuse of scientific and technical knowledge, making advanced designs significantly more accessible.

Our techniques could be used to ease the housing crisis for a wide range of other sites and species, from fire-affected animals to critically endangered wildlife such as the swift parrot or Leadbeater’s possum.

Kylie Soanes receives funding from The National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub and the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub. She is a board member of the Greater Melbourne Chapter of the Society for Conservation Biology.

Bronwyn Isaac, Dan Parker, Nick Bradsworth, Stanislav Roudavski, and Therésa Jones do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.