Undersea internet cables connect Pacific islands to the world. But geopolitical tension is tugging at the wires

Cable coming ashore from a ship. Coral Sea Cable System

If you’ve ever emailed a resort in Fiji or Vanuatu about that long-awaited holiday, it’s likely your email travelled through an undersea internet cable. Such cables carry much of the internet traffic around the globe, in conjunction with underground fibre connections, satellites and microwave links.

For Pacific Island countries, undersea internet cables can be crucial. The number of Pacific Island countries with such connections has increased substantially in recent years. Even so, many countries still rely on a single cable and others have no cable at all.

Each undersea cable is about the width of a garden hose, made up of protective layers of metal and plastic wrapped around the hair-thin optic fibres that carry signals as pulses of light. There are more than 400 submarine cables criss-crossing the world’s seabeds, with a combined length of 1.3 million kilometres.

The internet began as a US government project, and it is still dominated by the US today. As Chinese companies have become involved in laying undersea cables, geopolitics is influencing key decisions about the rollout of internet cables across the Pacific.

Aid and cables

Pacific Island countries are keen to improve their connectivity. In response, aid donors have been funding new cables.

Australia funded the Coral Sea Cable System for Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands that launched in December 2019. New Zealand supported the Cook Islands component of the Manatua cable, which landed in Cook Islands in September 2020.

Read more:

Fight for control threatens to destabilize and fragment the internet

Australia, the US and Japan are planning a second cable for Palau and Australia has provided funding to assess route options for Timor Leste’s first cable.

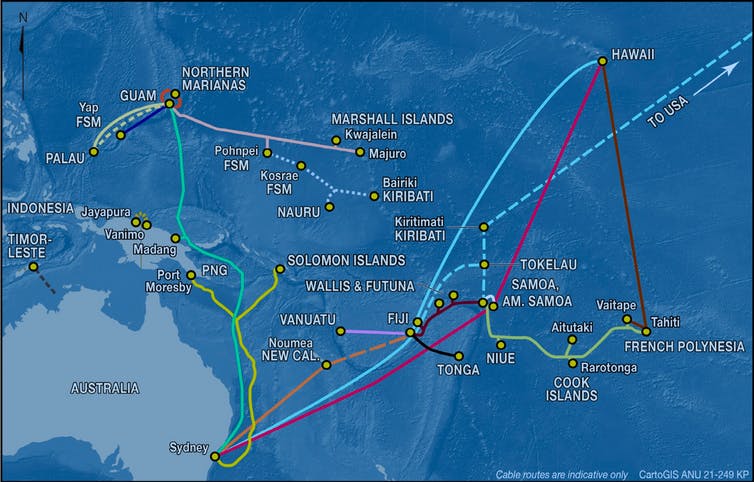

International undersea internet cables for Pacific Island countries.

Dr Amanda H A Watson and CartoGIS ANU, Author provided

Chinese companies shut out

The laying of undersea internet cables has become entwined with geopolitics.

A recent tender process for the East Micronesia cable, which was to be funded by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, elicited warnings from the US to the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru and Kiribati about “security threats posed by a Chinese company’s cut-price bid”. Such concerns may have been behind a decision to declare all three bids invalid.

Since then, Nauru has reportedly been considering a cable route that would connect to Solomon Islands (allowing internet traffic to flow on to Australia from there). Another possibility is that the US may step in to fund a cable following the same route as initially planned.

The Solomon Islands’ government had reportedly organised for a Chinese company to lay a cable from Solomon Islands to Australia, but the Australian government stepped in to fund the project instead. This move

“shut out Huawei Marine”, which had been contracted by Solomon Islands to do the work.

The cable comes ashore in the Solomon Islands.

Coral Sea Cable System

Security concerns

There are concerns in Australia and among allies about potential risks associated with China having access to, or control of, internet cables. Such concerns have increased since Chinese company Huawei started to lay undersea cables.

Taiwan has reportedly expressed similar anxiety:

Taiwan has claimed that China is backing private investment in Pacific undersea cable networks as a way to spy on foreign nations and steal data.

Similar concerns appear to be behind the cancellation of three planned cables, backed by Facebook and Google among others, that were to link to Hong Kong. Those plans changed after the introduction of Hong Kong’s extradition laws and other shifts in its political landscape.

The Hong Kong-Americas cable plan was withdrawn, a planned Hong Kong connection for the Pacific Light cable was abandoned and the Bay-to-Bay Express was also dropped.

US sanctions

The US Department of Justice has made its concerns clear:

a direct cable connection between the United States and Hong Kong would pose an unacceptable risk to the national security and law enforcement interests of the United States.

The US has imposed sanctions against Huawei and other Chinese companies. For its part, Huawei has repeatedly denied accusations of spying and links to the Chinese state and has offered to have its equipment tested.

In August this year, Chinese telecommunication company China Mobile pulled out of ownership of a cable that is to link the Philippines and the US. Sanctions against the company would have stopped the cable project from going ahead.

Geopolitics is not the only concern

As with the recent submarine announcement and other areas of collaboration, Australia could work with partner countries to establish strategic connectivity proposals. Ideally, plans for internet connections would put the needs of recipient countries and their citizens first. New internet infrastructure planning would also take into account the environmental consequences of both construction and operation.

Read more:

Australia to build nuclear submarines in a new partnership with the US and UK

However, in the current context, geopolitical considerations seem likely to weigh heavily on the minds of decision-makers.

The US dominates the internet and it is controlling the rollout of internet cables in the Pacific and elsewhere.

It remains to be seen what this will mean for people in Pacific Island nations. If traditional partner countries consult with local leaders about what they want, then all may be well. Time may reveal whether internet access in the Pacific region is held back by geopolitical tensions.

Amanda H A Watson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.