A simple calculation can stop artificial intelligence sending you broke

Shutterstock

Mike is a 40-something crop farmer from southern Queensland. With a chestnut tan, crushing handshake and a strong outback accent, he’s the third generation of his family to grow sorghum, a cereal mostly used for animal fodder.

But, like most farmers, Mike faces more challenges than his forbears. Climate change has eroded Australian farms’ profitability by an average of 23% over the past 20 years. It’s a constant challenge to improve productivity by producing more with less.

Read more:

Australian farmers are adapting well to climate change, but there’s work ahead

After the devastating 2019 bushfire season, Mike began exploring “smart” farming techniques enabled by artificial intelligence (AI). Agriculture has been called one of the most fertile industries for AI and machine learning. Mike was enthused about an AI powered system enabling him to use less fertiliser and water.

After months of inquiries he found a company promising its technology could reduce crop inputs by up to 80%. It involved software processing information from digital sensors placed across his fields to allow “precision farming” – tailoring water, pest and fertiliser treatment for each plant.

The salesperson’s pitch was compelling. But the cost to install the system was $500,000, plus $80,000 a year for data storage and processing. Support costs were on top of that.

Ultimately, Mike calculated the cost would offset any extra profit generated, even if the slick technology lived up to all the promises. If it delivered less, it would only help him into bankruptcy.

This experience – of being pitched an AI technology with big claims but questionable value – is common. It’s easy to be swayed by the promises. But new technology is not the solution to everything. For it to be worth the money for people like Mike – indeed any organisation – requires a cold calculation of its economic value.

In this article we provide a simple methodology to do so.

Blinded by technological potential

For all the focus now on how AI will revolutionise the world, hype about it isn’t new. Since the inception of practical AI techniques in the early 1960s, obsession with AI potential has led to two major “AI winters” – in which huge investments by corporations and research institutions failed to deliver promised results.

The first was in the 1970s, when money poured into variety of AI systems such as speech recognition and machine translation. The second was in the 1980s, when companies invested heavily in so-called “expert systems” meant to do things like diagnose illnesses or control space shuttle launches.

Computer scientist John McCarthy, who coined the term ‘AI’, at work in his laboratory at Stanford University.

AP

In both cases what the technology could do fell well short of the hype. It was not that AI was useless. Far from it. But what it could do had limited economic value.

The backlash set the scientific and economic advance of the technology back almost a decade both times, as funding and interest dissipated.

To be sure your investment in technology is worth the money, you need to guard against being swept up by the promises and possibilities.

As Ben Robinson, then chief strategy officer at financial software company Temenos, put it in 2018:

we can safely predict it won’t be blockchain or APIs or AI that transform the industry. Instead it will be new business models empowered by those technologies.

Read more:

If machines can be inventors, could AI soon monopolise technology?

Focus on the economics

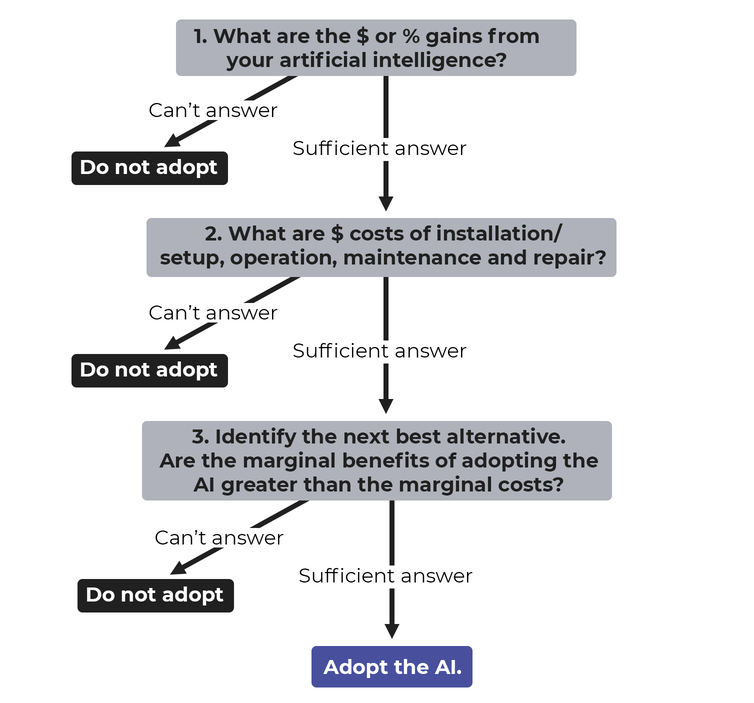

The following figures outline a simple approach to focus on the economics, not the engineering.

Figure 1 summarises the basic economics of any investment decision. Invest if the extra profit is greater than the “opportunity cost” – the benefit you can gain from spending your money another way, or by not spending the money.

Figure 1 can be hard to use so Figure 2 frames the investment decision in slightly more detailed terms using the economic concept of “marginal utility” – the additional (marginal) benefit (utility) that comes from additional expenditure.

To make this simple to apply, Figure 3 summarises this decision-making process into a simple “decision tree”.

The Conversation/Author provided, CC BY-ND

Resolving Mike’s AI investment challenge

Applying this methodology to Mike’s situation, we can see why he couldn’t make business sense of the pitch of AI-enabled precision farming.

The salesperson passed the first question by stating the gains from AI adoption would reduce Mike’s crop input costs by up to 80%. This would translate to Mike saving about $80,000 per year (in the best-case scenario).

The salesperson also passed the second question, with a clear statement of the system’s cost.

But the business case failed on the third question. The best-case marginal benefit of adopting the AI (saving $80,000 a year) was just equal to the marginal cost ($80,000 a year) – not counting the initial installation.

Read more:

Artificial intelligence is now part of our everyday lives – and its growing power is a double-edged sword

Putting it this way makes it clearly look like a dud investment, and that Mike didn’t have put a lot of time into deciding against it. But the fact is many decisions to invest in AI don’t make economic sense and the above process will make this easy to know why.

Using an economic framework of worth, rather than an engineering claim of possibility, is the first step to make better decisions. Doing so reduces the prospect of another AI winter, and increases the chance of real gains contributing to a more prosperous and sustainable world.

Evan Shellshear is head of analytics at Biarri, a mathematical and predictive modelling company.

This article was co-authored by Brendan Markey-Towler, previously a lecturer and research fellow at The University of Queensland and now an analyst with Westpac. All three authors declare they do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. This story is part of a series on financial and economic literacy funded by Ecstra Foundation.