After 20 years of patience and negotiations, RPG veteran Brian Fargo managed to buy back a lost haul of memorabilia from Fallout, Baldur's Gate, and more: 'It was like a very exciting version of Storage Wars'

Christmas came early this year for Interplay co-founder and inXile Entertainment studio head Brian Fargo. In a series of tweets last month on X, “The Everything App,” Fargo showed off industry sales awards and other Interplay goodies he had recently re-acquired. Over email, Fargo explained to me how they had left his possession in the first place, and the long march to get them back.

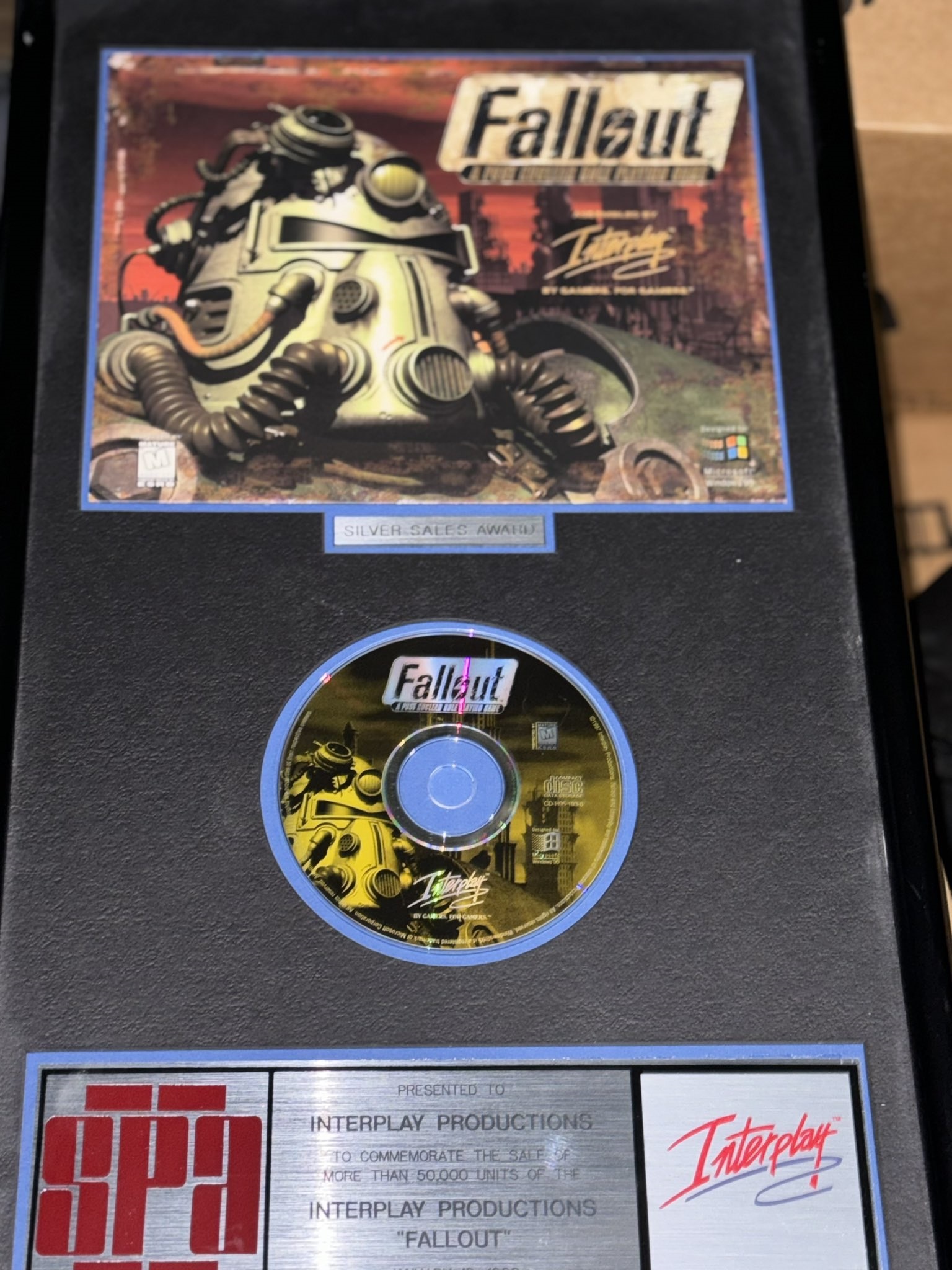

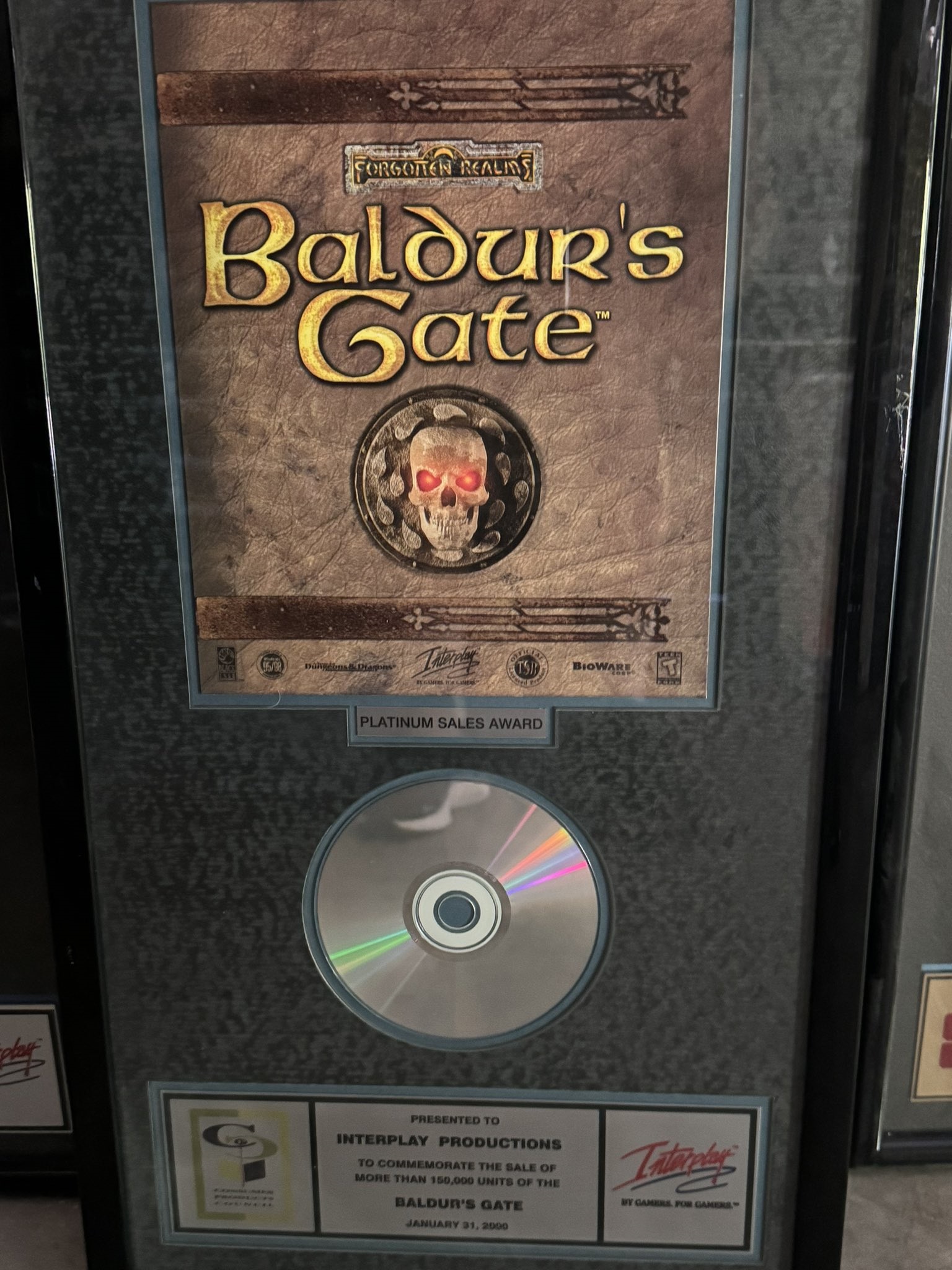

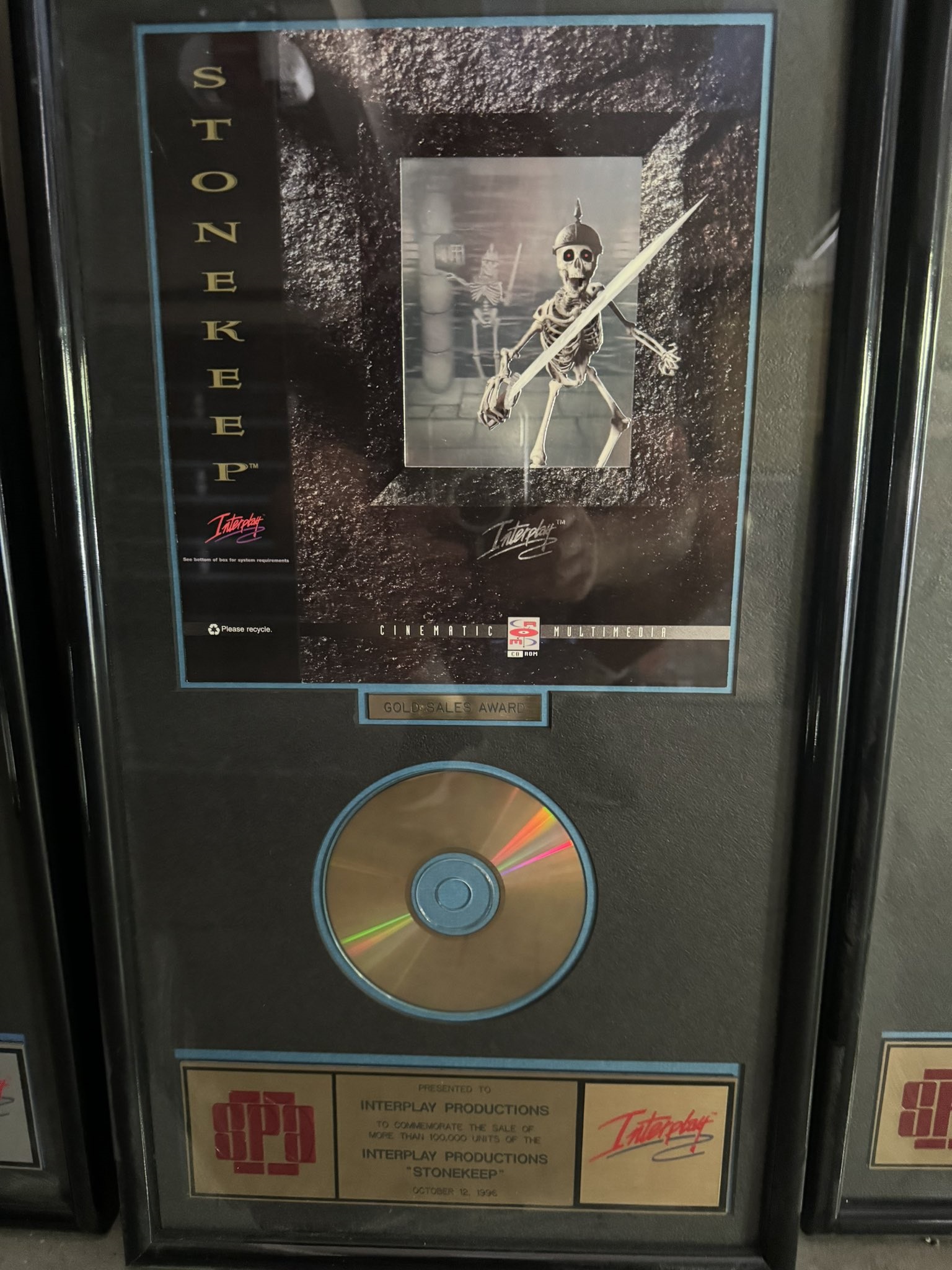

First though: The trove itself. Most of the items Fargo showed off were sales awards for various Interplay games from the Software Publishers Association (now the Software and Information Industry Association) of “Don’t Copy that Floppy” fame. The OG Baldur’s Gate plaque, meanwhile, came from the Consumer Products Council, a decidedly less musical industry body.

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

As Fargo pointed out on Twitter, those sales numbers definitely seem quaint in comparison to modern blowouts like Black Myth: Wukong’s staggering 10 million units in one week: “Back in the day, you’d get an award for selling 50 or 100,000 units,” Fargo wrote. “Now it’s the end of your career.”

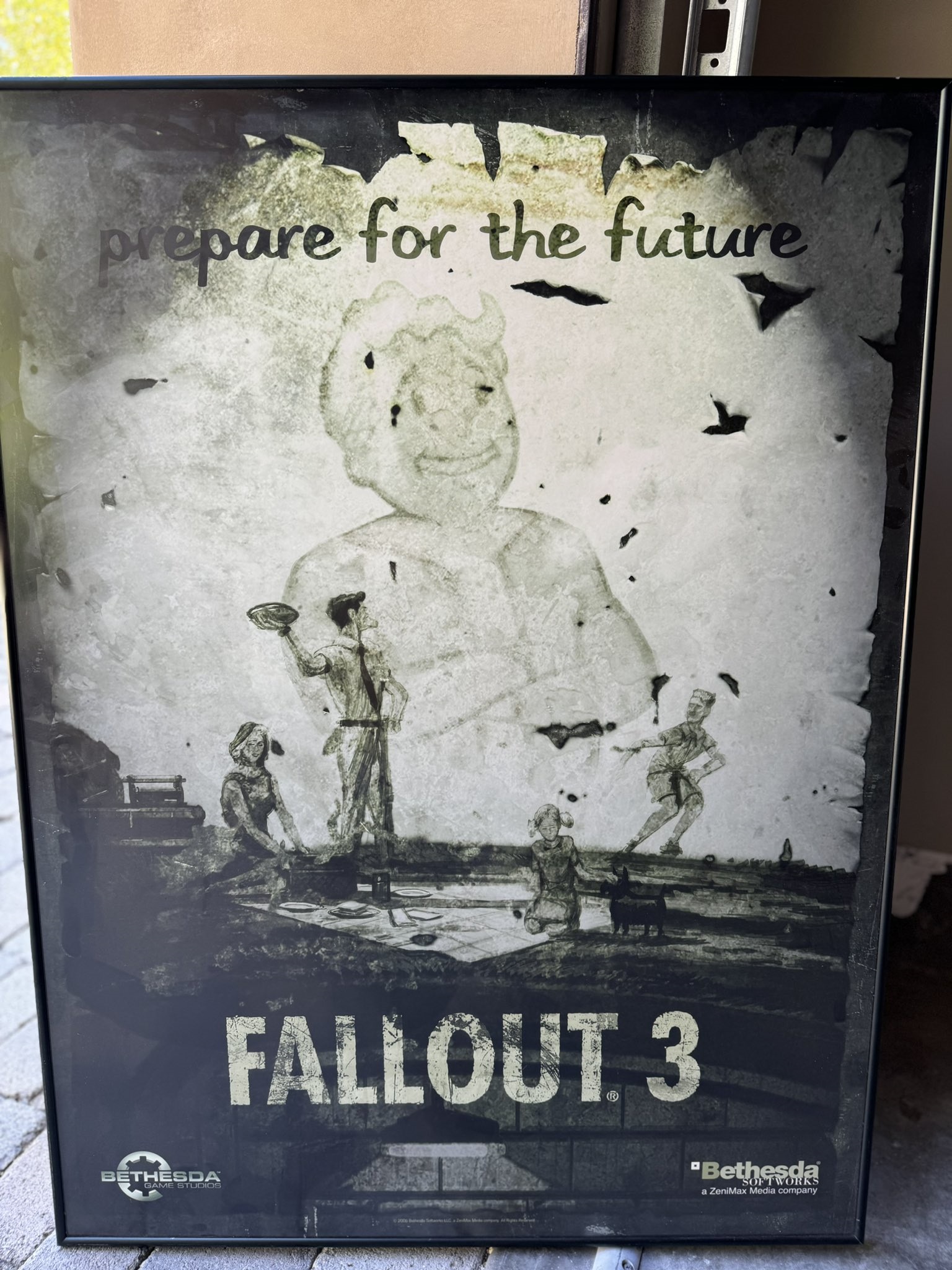

There are two outliers in the pictures Fargo shared: A Fallout 3 poster from after Bethesda took over the series, and a mammoth, six foot-tall poster of Baldur’s Gate 1 baddie Sarevok—he should also look familiar to any new school kiddies who only checked out the third game. That Sarevok is definitely the piece of the collection that earned my gaming tchotchke envy, but I am once again reminded that a large part of Baldur’s Gate 1’s plot revolves around the people of the titular city wanting this clearly evil spiky armor guy to be mayor. Democracy has its flaws.

“When I left Interplay [in 2002] I was not able to take many things with me, they were the property of the company,” Fargo told me over email. “That’s just how it works sometimes but obviously I had an emotional attachment to the memorabilia and knew that the current owner did not.

“It’s never easy when such a corporate split happens, so I knew I’d have to wait a decade-plus for emotions to reduce, so I didn’t even start asking about acquiring the things in the warehouse until around 10 years ago.”

After that thaw, Fargo said it took another decade of “asking, cajoling, and humoring” Interplay CEO Hervé Caen to let him buy back the merchandise. “Finally we met, agreed on a price and then it took another 3 months! I was very happy when I finally got them as you might expect.

“It was like a VERY exciting version of Storage Wars. I only knew partially what was in there.”

As for Fargo’s favorite piece of the collection, the Fallout sales award from the SPA looms large, but he has a soft spot for the awards for older, less-remembered games like Battle Chess and Castles that were “critical to [Interplay’s] survival.”

“There were several times in the history of Interplay in which the company would have gone under had the game not succeeded,” Fargo recalled. “Battle Chess was our first published game in which we financed the development, manufacturing, and marketing, all chips were on the table. Castles was the same except in terms of finance risk, but it represented our first game for which we went direct to retail (Battle Chess was distributed by Activision).

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

(Image credit: Brian Fargo)

“Activision was going bankrupt at the time and could not pay the money owed to us, so we were back in a perilous position, and to make matters worse, retailers were making us give them credit for inventory for games that Activision didn’t pay us for, so it was a double hit. A very scary time.”

There are still a few lost treasures from Interplay that Fargo hopes to find: First are any of the clay sculpts used for Fallout’s “Talking Head” NPCs. The models by Scott Rodenhizer were posed and digitized to make the key frames of sprites, a rendering style reminiscent of stop-motion animation that many other ’90s games (including Doom and Donkey Kong Country) experimented with before the advent of full 3D graphics.

“The other thing that I tried to acquire were the design and vision documents from the games,” Fargo said. “That would have been a nice insightful look into the thought genesis of the classic Interplay games.”