Australian writers have been envisioning AI for a century. Here are 5 stories to read as we grapple with rapid change

Shutterstock

Australians are nervous about AI. Efforts are underway to put their minds at ease: advisory committees, consultations and regulations. But these actions have tended to be reactive instead of proactive. We need to imagine potential scenarios before they happen.

Of course, we already do this – in literature.

There is, in fact, more than 100 years’ worth of Australian literature about AI and robotics. Nearly 2,000 such works are listed in the AustLit database, a bibliography of Australian literature that includes novels, screenplays, poetry and other kinds of literature.

These titles are often overlooked in policy-driven conversations. This is a missed opportunity. Literature both reflects and influences thinking about its subjects. It is a rich source of insights into social attitudes, imagined scenarios and what “responsible” technology looks like.

As part of an ongoing project, we are creating a comprehensive list of Australian literature about AI and robots.

Here are five Australian literary works of particular relevance to national conversations about AI.

The Automatic Barmaid

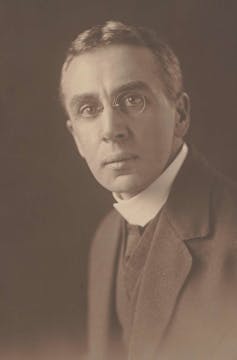

The Automatic Barmaid is a short story by Ernest O’Ferrall, who wrote under the pen name “Kodak”. Like his contemporaries Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson, Kodak was best known as a writer of comedic bush stories.

Ernest O Ferrall (1881-1925).

Robin M. Cale/National Library of Australia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This particular story was published in The Bulletin in 1917 and is available for online reading through Trove.

The story concerns an automaton named Gwennie, who at first seems too good to be true, as she is cheaper and more efficient than a human barmaid. But Gwennie soon causes trouble by getting stuck on problems that humans could easily solve, like not realising a bottle is empty.

The Automatic Barmaid is a humorous depiction of robots as tempting and cheap but not always suitable replacements for human labour. It is no coincidence the story was published in 1917, just before the Great Strike: the culmination of waves of strikes that occurred during the first World War.

One of the triggers for the Great Strike was the use of time and motion studies, especially by rails and tram companies, in which workers’ activities were timed to evaluate performance. Gwennie would have performed perfectly in these studies.

Today, most Australians do not trust AI in the workplace, particularly when it comes to HR tasks like monitoring, evaluation, and recruitment. The Automatic Barmaid shows how persistently sceptical we have been about our technologies over the last century, and how much we value human workers’ adaptability and resilience.

Most Australians do not trust AI in the workplace.

Shutterstock

The Successors

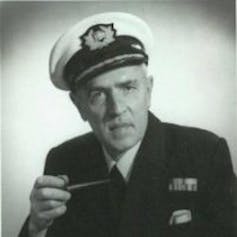

A. Bertram Chandler was a sailor turned science-fiction writer, who published prolifically from the mid-1940s, particularly in his Rim Worlds series.

His 1957 short story The Successors begins with a general and a professor meeting while their planet – presumably Earth – is under attack from an unknown race of invaders. These two characters initially seem to be humans at some point in the future, but they are later revealed to be part of a race of robots that overthrew humanity.

The robots have enslaved the humans who once enslaved them. The professor muses that, in the end, the humans and the robots are not so different after all.

A. Bertram Chandler (1912-1984).

Hachette Australia.

The Successors explores an as yet unachieved scenario. It imagines Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Most current AI systems are what we call “narrow”, and can only complete a limited number of tasks in specific areas. For example, a chess-playing AI could not be expected to make investment recommendations.

We are, however, moving towards AGI: AI systems that can complete a wide range of tasks across various areas. A robot that can walk around, speak and overthrow humanity would be an example of AGI.

Australian MP Julian Hill has spoken openly about the risks and benefits of AGI, arguing that “action by governments to grapple with the impact of AGI is now urgent”.

Although many people believe that AGI is still a long way into the future, thinking about extreme future scenarios, like the one in The Successors, can help us identify where we might need to mitigate risk. These scenarios can also give us insight into our present concerns about technology, inviting us to consider what we are afraid of and why.

Read more:

Nuclear bombs, artificial intelligence and the madness of reason – in The Maniac, Benjamin Labatut examines the troubling dawn of the digital age

Moon in the Ground

Keith Antill’s novel Moon in the Ground was published by pioneering Australian science fiction press Norstrilia in 1979. It is about an extraterrestrial AI that can adapt its physical form to its environment.

This AI is discovered near Alice Springs by American FBI agents, who try to train it for militaristic use on a nearby base. A struggle between the Americans and the Australians ensues, with both trying to harness the power of the AI for their own political aims.

The novel is a response to the political climate of the time. When it was published, the Cold War was ongoing. In the story, the US is depicted as paranoid about communism and desperate for global power.

Moon in the Ground speaks to the longstanding connections between defence and robotics, autonomous systems and AI – connections that Australia is now looking to strengthen.

It also illustrates the connection between technology and political power: a connection that Antill, formerly of the Royal Australian Navy and later a public servant, would have seen firsthand. Access to the newest, most advanced technologies can help a country gain power over others. However, as Moon in the Ground shows, chasing that power too keenly can be destructive.

The Tic-Toc Boy of Constantinople

The Tic-Toc Boy of Constantinople, a short story by Anthony Panegyres, was published in 2014 as part of the steampunk collection Kisses by Clockwork.

The story centres on Phyte, a robot who looks and acts like a human boy, apart from having a metal plate on his chest and occasionally producing steam. He is feared by everyone except his human creator, who intended him to be a test site for the creation of artificial organs that could be transplanted into humans.

It turns out people are right to be afraid, as the human-clockwork hybrids (of which Phyte is one) have a primal urge to kill the humans that help them.

The Tic-Toc Boy of Constantinople encourages us to think about how bodies are central to our experiences of the world. Like many steampunk works, it emphasises the long history of biomechanical enhancements and adjustments to human bodies.

As Australia works towards integrating AI in healthcare, we need to think about how technologies interact with our bodies, and ensure that commercial interests do not overshadow public benefit.

AI technologies can help us better care for our bodies by complementing the work of medical professionals. However, as wearable and implantable technologies become more common, reflecting on the ways we are augmenting our bodies will ensure that we are more than just test sites for other people’s plans.

Read more:

‘Cli-fi’: could a literary genre help save the planet?

Clade

James Bradley’s 2015 cli-fi novel Clade follows a family from the near future living in an increasingly precarious and unpredictable world faced with ecological collapse. AI plays a relatively minor part in the narrative, but when it does appear, it is represented ambivalently.

Dylan works for a company called Semblance that builds AI simulations, also called sims or echoes. These are virtual recreations of the dead assembled from as much data as available.

The sims can read and mimic the responses of people who interact with them. “They’re not conscious, or not quite,” the narrator explains. “They’re complex emulations fully focused on convincing their owners they are who they seem to be.”

Initially something of a gimmick, the sim business becomes very lucrative as more people die in the book. Over time, though, customers want to tweak their sims. The customers start making the dead less like they were and more as they would have preferred them to be.

Dylan’s dad thinks his son’s work is exploitative, profiting as it does from vulnerable people. Dylan faces his own ethical dilemma when he comes across a request to build a sim of an ex-girlfriend’s brother.

As the Australian Government works towards policies related to AI, and generative AI more particularly, attention to ethical development is becoming more prominent.

Clade encourages us to think about where our boundaries might be and why. The technology Dylan works to develop already partially exists. Does this technology best serve Australians? If not, how can we make it so?

Making sense of the world

Humans tell stories to make sense of the world. Literary representations have much to tell us about how we understand and respond to the rapidly advancing and seemingly unpredictable technology of AI.

To develop AI and robots that best respond to the needs of Australians, we can learn a lot from reading our own literature.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.