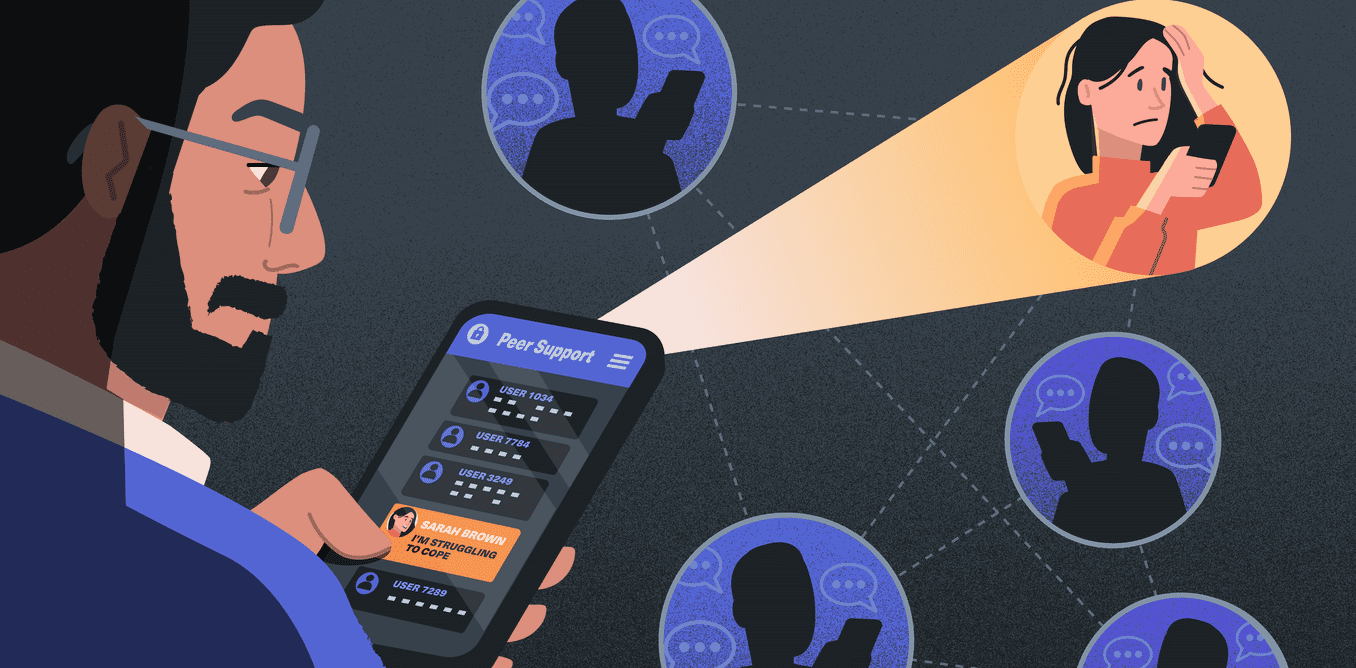

Charities are contributing to growing mistrust of mental-health text support — here’s why

Johnny Lighthands, Author provided

Like many areas of society, mental healthcare has changed drastically as a result of the pandemic. Forced to adapt to a growing demand for counselling and crisis services, mental health charities have had to quickly increase their digital services to meet the needs of their users.

Unfortunately, some charities have experienced growing pains as they transition to an unfamiliar environment that increasingly involves the use of data-driven technologies, such as machine learning – a type of artificial intelligence.

Recently, two charities faced a public backlash as a result of how they used machine learning and handled data from users who contacted their mental health support services at a point of crisis.

When it was revealed that US-based Crisis Text Line shared users’ data with another organisation – Loris AI – that specialises in the development of machine learning technologies, there were many critical responses on social media decrying the commercialisation of sensitive data as a shocking betrayal of trust. In response, Crisis Text Line ended its data-sharing relationship with Loris AI and asked the company to delete the data it had sent.

A couple of weeks later, it came to light that Shout, the UK’s biggest crisis text line, had similarly shared anonymised data with researchers at Imperial College London and used machine learning to analyse patterns in the data. Again, this data came from the deeply personal and sensitive conversations between people in distress and the charity’s volunteer counsellors.

One of the primary reasons behind this partnership was to determine what could be learned from the anonymised conversations between users and Shout’s staff. To investigate this, the research team used machine learning techniques to uncover personal details about the users from the conversation text, including age and non-binary gender.

The information inferred by the machine learning algorithms falls short of personally identifying individual users. However, many users were outraged when they discovered how their data was being used. With the spotlight of social media turned towards them, Shout responded:

We take our texters’ privacy incredibly seriously and we operate to the highest standards of data security … we have always been completely transparent that we will use anonymised data and insights from Shout both to improve the service, so that we can better respond to your needs, and for the improvement of mental health in the UK.

Undoubtedly, Shout has been transparent in one sense – they directed users to permissive privacy policies before they accessed their service. But as we all know, these policies are rarely read, and they should not be relied on as meaningful forms of consent from users at a point of crisis.

It is, therefore, a shame to see charities such as Shout and Crisis Text Line failing to acknowledge how their actions may contribute to a growing culture of distrust, especially because they provide essential support in a climate where mental ill-health is on the rise and public services are stretched as a result of underfunding.

An unsettling digital panopticon

As a researcher specialising in the ethical governance of digital mental health, I know that research partnerships, when handled responsibly, can give rise to many benefits for the charity, their users, and society more generally. Yet as charities like Shout and Crisis Text Line continue to offer more digital services, they will increasingly find themselves operating in a digital environment that is already dominated by technology giants, such as Meta and Google.

In this online space, privacy violations from social media platforms and technology companies is, unfortunately, all too common. Machine learning technology is still not sophisticated enough to replace human counsellors. However, as the technology has the potential to make organisations more efficient and support staff in making decisions, we are likely to see it being used by a growing number of charities that provide mental health services.

In this unsettling digital panopticon, where our digital footprints are closely watched by public, private and third sector (charities and community groups) organisations, for an overwhelming variety of obscure and financially motivated reasons, it is understandable that many users will be distrustful of how their data will be used. And, because of the blurred lines between private, public and third-sector organisations, violations of trust and privacy by one sector could easily spill over to shape our expectations of how other organisations are likely to handle or treat our data.

The default response by most organisations to data protection and privacy concerns is to fall back on their privacy policies. And, of course, privacy policies serve a purpose, such as clarifying whether any data is sold or shared. But privacy policies do not provide adequate cover following the exposure of data-sharing practices, which are perceived to be unethical. And charities, in particular, should not act the same way as private companies.

If mental health charities want to regain the trust of their users, they need to step out from the shade of their privacy policies to a) help their users understand the benefits of data-driven technologies, and b) justify the need for business models that depend on data sharing (such as, to provide a sustainable source of income).

When people are told about the benefits of responsible data sharing, many are willing to allow their anonymised data to be used. The benefits of responsible research partnerships include the development of intelligent decision-support systems that can help counsellors offer more effective and tailored support to users.

So if a charity believes that a research partnership or their use of data-driven technologies can lead to improved public health and wellbeing, they have legitimate grounds to engage users and society more broadly and rebuild a culture of trust in data-driven technologies. Doing so can help the charity identify whether users are comfortable with certain forms of data sharing, and may also lead to the co-development of alternate services that work for all. In other words, they should not hide behind vague privacy policies, they should be shouting about their work from the rooftops.

Christopher Burr receives research funding from the UKRI's Trustworthy Autonomous System's Hub.

He is chair of an IEEE research programme that explores the ethical assurance of digital mental healthcare.