Esports: how the struggling hospitality industry could capitalise on this massive business

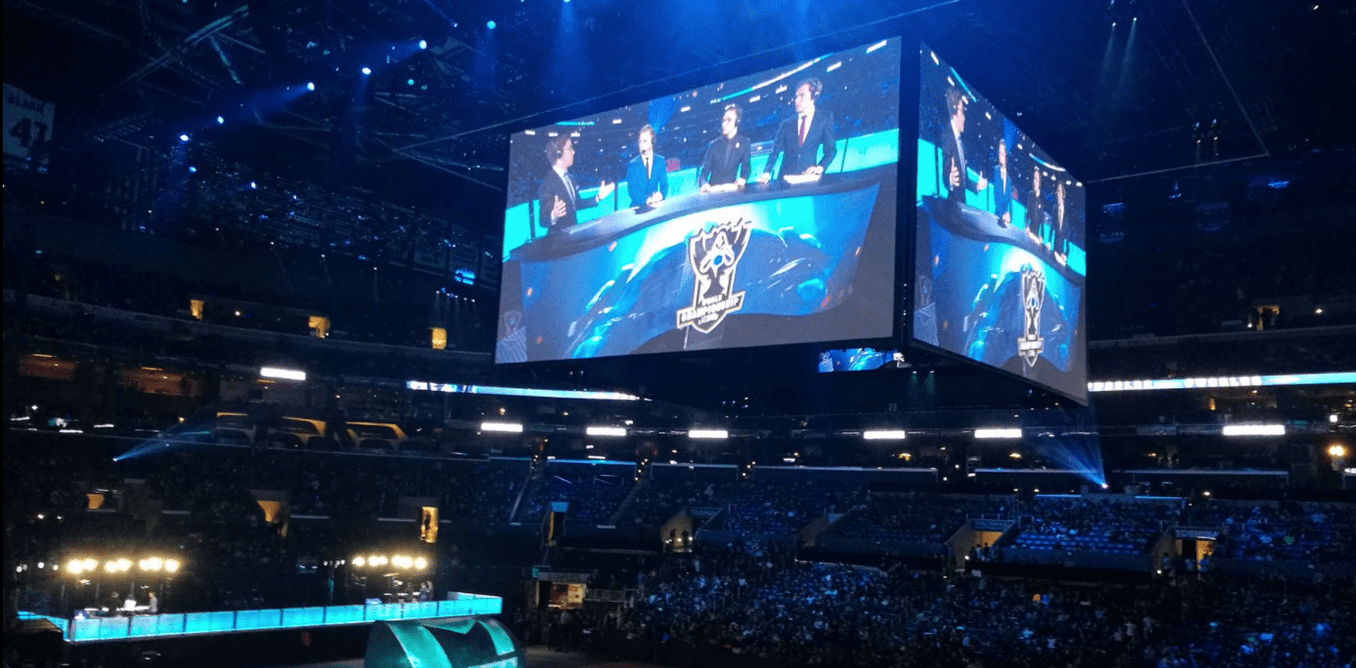

The League of Legends world championship at the Staples Center Los Angeles in 2016. Patrick Knight/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

During the pandemic, the sporting world ground to a halt. Global events such as the Olympics, Formula 1 racing, the UEFA Champions League and American basketball were all postponed.

As an alternative, Formula 1 launched a virtual grand prix series featuring professional F1 drivers. Similarly, Leyton Orient football club organised an online FIFA tournament.

This competitive online video gaming is known collectively as esports and brings excitement and competition at a time when traditional sporting events are unable to. The explosion in popularity during COVID-19 meant the global virtual audience of esports exceeded 700m fans in 2021.

At the same time, hospitality and tourism sectors experienced the opposite fate. Continual lockdowns led to a sharp decline and the almost complete shutdown of tourism activity for many months.

When professional sport resumed once again, the majority of matches and events were played behind closed doors. With no fans or tourists attending games, mass global events including the Tokyo 2020 Olympics received little income.

Mega sporting events normally lead to a spike in spending on food, drink, hotels, parking, concessions and merchandise. However, online viewership only meant cancelled travel plans and bookings to host cities.

So, with a fast-growing esport industry and a tourism sector just beginning to recover from lockdown, shouldn’t the hospitality industry be actively attracting esport fans? In our research, we wanted to look at how the industry can capture the esport fanbase and convert them into active tourists. We surveyed 549 fans of competitive esport video game League of Legends alongside a 12-month observational study of active World of Warcraft players.

Esports, fans and live events

At its peak, the League of Legends’ 2021 world championship had over 4m online viewers. Yet, despite substantial online audiences, even pre-pandemic, only a small fraction of esport revenue came from ticket sales, meaning few fans are willing to travel to live events.

There are some arenas that have generated large crowds, such as Korea’s Sangam Stadium. The experience for these spectators can be truly captivating. Huge immersive screens are set up to show the competitive game play between teams, amplifying the excitement and tension in the crowd.

However, by not actively seeking esport viewers, the tourism and hospitality industry risk alienating a growing global fanbase. This means the opportunities offered by the attractive and potentially lucrative market may be lost.

Esport teams such as Na’Vi; Alliance; T1; KT Rolster; OpTic and FaZe enjoy fierce rivalries playing Dota 2, League of Legends, and Call of Duty. Loyal fans and spectators are passionate about their favourite teams and branded merchandise is becoming big business for esports.

There is an opportunity here for host cities to offer activities and events specifically for those attending competitive esport events. It is worth considering, for example, special team-specific fan zones and social spaces to capitalise on the loyalty of passionate followers. They bring passion and excitement to a sporting event, making them unmissable events for those who consider themselves diehard fans.

Building enthusiasm for events

Esport is experienced online as a social community. Yet, for the most part, it is consumed without any actual proximity to other spectators.

This means a potential spectator is more likely to be travelling alone or hoping to meet up with online friends in person for the first time. This makes buying tickets and travelling to an event a daunting prospect for many.

However, local event providers could do more by offering forums and discussion channels that could build enthusiasm and anticipation in the run-up to the event. These online spaces would also give fans a chance to seek advice and support on where to stay and what to do, making the transition from online to offline much less daunting.

The tourism sector needs to encourage the online video game audience to attend big live events and capitalise on the potential spending.

Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

The esport calendar is dominated by prestigious world championship competitions such as League of Legends, StarCraft II and Crossfire. Much less enthusiasm is generated for smaller qualifying or regional competitions. In fact, they usually take place exclusively online.

Travelling internationally to competitions can be less appealing to many fans. The cost of attending large sporting events is high, particularly for esport’s predominantly younger audience.

Local events could offer an entry point to first time live event spectators – building a passion for experiencing esport competition in-person.

The draw of star players

Esport prize money and salaries are growing substantially. The winners of the biggest DOTA 2 esport tournaments have taken home over $5 million (£3.8 million) in prize money.

This makes them big-time celebrities by any metric, and their attendance at events can be a big draw for fans. Meeting and interacting with star players is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and needs to be part of the esport promotional strategy.

Event organisers could offer some additional fan viewing opportunities to see players practise and warm up. This would give greater value to the live event experience versus watching online.

The growth in esports shows no sign of slowing down, but live events are yet to take off to the same extent as online viewership. If tourism and hospitality can attract even a small fraction of esport’s 700m online viewership, then this could be a significant new revenue stream for cities hosting these events.

Mega esport competitions could become mass flagship events in the sporting calendar. These events have the potential to book out whole stadiums, which benefits hotels, bars, shops and local tourism. In the wake of the pandemic, tourism everywhere is suffering. The hospitality industry needs to get creative and seek out new opportunities like esport, and tempt massive online audiences to experience their passions in the real world.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.