Gamergate and the bodice-ripper have little in common, with respect

How do men feel about the way they are depicted on the covers of romance novels? Book Thingo

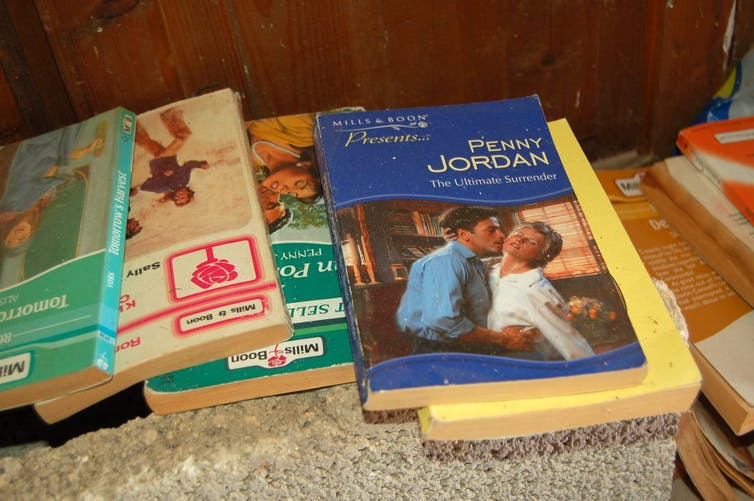

Buttons open to the waist, skin gleaming with sweat, hair tousled, intriguing flashes of curves … men on the covers of classic romance novels, or “bodice rippers”, are objectified in many of the same ways that women are in gaming. Men are painted as brutal, sex-obsessed and not averse to a little (or a lot) of rape and pillage. Women are often portrayed as willing participants even as they pant “No”.

Recently Christian Fonnesbech, director of the critically acclaimed game, Cloud Chamber, posed a question on Twitter:

Are realistic women in fantasy games and realistic men in romance novels two sides of the same coin?

The tweet was accompanied with an illustration of the kind of book cover to which he was referring.

Twitter

The question feeds into Gamergate, which – for those who don’t know – is ostensibly a movement about gamer identity and journalism ethics which has morphed into an examination of the way women in the gaming industry are treated by other gamers.

Given the person asking the question is a serious player in the independent gaming industry I felt I had to consider his question seriously rather than simply snort inelegantly in disdain. So here I go.

My initial response as a media scholar is that the way we portray the “other”, whether it is gender or race or social identity does matter. But it matters more when a power imbalance exists between the content creator and image or words, or the portrayer and portrayee. And it matters even more when the portrayal is linked to real life social behaviour.

It is all about who is allocated authority to describe the other and what they do with that. Even a kindly depiction of the other can be offensive if it is a colonising view. It becomes the person with power describing their subjects or handing down judgments about permissable portrayals and behaviours.

You have to ask how men feel too about the way they are depicted on the covers of romance novels. Do they find them alienating or offensive? Who selects and creates these book covers? Are they selected and created by men with a largely female audience in mind? Or are they created by women for women? And does this make a difference?

Feminist blogger Anita Sarkeesian recently posted what one week on Twitter looks like for her. This included 157 abusive tweets, with 24 explicit threats of rape or violence. More worrying was the insistence by at least one of the commenters that rape and violence are part of gaming.

I don’t have statistics on the number of men abused verbally or otherwise as a result of racy portrayals on book covers – which is not to deny the existence of female violence towards men. At least in Australian society, however, violence towards women by men is not only pervasive, but common.

Destroy the Joint’s “Counting Dead Women Project” found that one woman is “killed almost every week by her current or former partner in Australia.” (89 women between 2008 and 2010). If you are disinclined to trust a “radical” group’s figures, consider instead the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2012 Personal Safety report that 4.5% of Australian men over the age of 15 had experienced sexual violence compared with 19.4% of women over the same age.

Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women (ANROWS) stacks up some sobering figures here. Most concerning is the fact that young women (18-24 years old) experience sexual assault at twice the rate of the female population. Men are much less likely to experience sexual violence of any kind than women, but much more likely to experience physical violence from other men. That however, is a discussion for another time.

Or if you prefer economic analyses, consider that the Federal Government in 2014 presented evidence that: “Domestic violence and sexual assault perpetuated against women costs the nation $13.6 billion each year.”

Robert Wallace

This is what is concerning about men (mostly) arguing that the way women are portrayed in gaming is just part of the culture and the game: that it is too close a mirror of everyday life. Correlation not being causation, we can’t say that such depictions in games cause violence.

In fact, decades of academic research has not been able to conclusively demonstrate a link between violent media and violent behaviour in individuals because so many confounding factors exist.

However a 2005 Lancet meta-analysis concluded that: “there is evidence that violent imagery has short-term effects on arousal, thoughts, and emotions, on increasing the likelihood of aggressive or fearful behaviour.”

More interestingly, in that same meta-analysis Browne and Giachritsis highlight research that demonstrated that aggressive behaviour after playing violent video games increased when games had human characters.

The same study found that cartoons with violence have been shown to have a significant effect on behaviour, topped only by media that portrayed a combination of violence and erotica.

You could also look at the role of storytelling, both the stories told and how they are told, in creating ways of thinking and talking that become social norms, or “common sense”. If you want to take another approach, you could think about how repetitive portrayals of people in certain ways create easily accessible cognitive schemas.

If all the women you “know” online are sexual objects and schemers only interested in what they can get out of you, how does this translate to how you interpret your everyday interactions with real-life women?

In addition to the research mentioned above, you can also say that such portrayals of women as objects to be used as one wishes are offensive, alienating. They say something quite profound about the people who prefer the “other” to be depicted in such a manner.

Ultimately there isn’t a fundamental difference in the images being produced by game creators and romance writers (or their graphic production team). The difference is how that portrayal affects the viewer/reader/gamer and what they do with such portrayals.

You may even wish to argue that people should “toughen up” if they want to be full participants in the gaming world. Interestingly it is only women who are expected to “toughen up”. The men are doing it for fun.

I argue instead that if you are concerned about others’ wellbeing and positive social outcomes, then how women are portrayed and interacted with anywhere, whether online or in real life, matters. And if you possess or have taken, for whatever reason, the authority to describe others, it does come with a responsibility to respect, or at least try to understand, them.

That is what is clearly missing in #gamergate, to an extent not nearly so obvious as those book covers.

Jenny Ostini receives funding from the Australian Government’s Collaborative Research Networks (CRN) program. ‘Digital Futures’ is the CRN research theme for the University of Southern Queensland. She is affiliated with 612 ABC Brisbane Local Radio as a Community Correspondent.