If machines can beat us at games, does it make them more intelligent than us?

Computers are getting better at playing games such as chess. Shutterstock/Vasilyev Alexandr

The year 1997 saw the ultimate man versus machine tournament, with chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov losing to a machine called Deep Blue.

Earlier this year, in what was hailed as another breakthrough in artificial intelligence (AI) research, Google’s AlphaGo defeated a professional Go player.

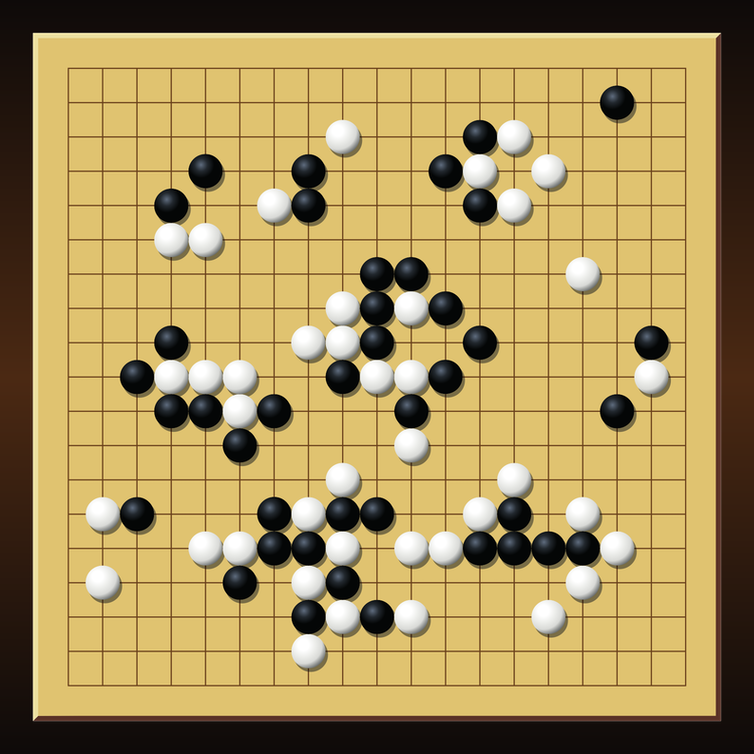

Go is an ancient Chinese board game that has hitherto been difficult for a computer to play at a high level due to its deceptively complex gameplay. Where chess is played on a board of 8 x 8 squares, Go is typically played on a board of 19 x 19 squares.

The 19 x 19 Go game board.

Shutterstock/Peter Hermes Furian

These are all worthy engineering achievements, but what does it mean for research into genuine machine intelligence and the predicted artificial intelligence that will surpass human intelligence?

Arguably, not much. To understand why, we need to delve a little more into the complexity of the games and the differences between how machines and humans play.

It is estimated the number of possible games of chess is 10120 while the lowest limit of games for Go is 10360. These numbers are big, even for a computer. If you’re not quite convinced of this, the estimated number of atoms in the observable universe is merely 1079 – minuscule in comparison.

Game-playing AI still cannot foresee every possible game play and, just like us, has to consider the options and make a decision on what move to make. For brevity, we’ll mainly stick with chess as it’s more widely known. Let’s look at how a computer plays first.

The machine

Most chess programs operate via brute-force search, which means they look through as many future positions as they can before before making a choice.

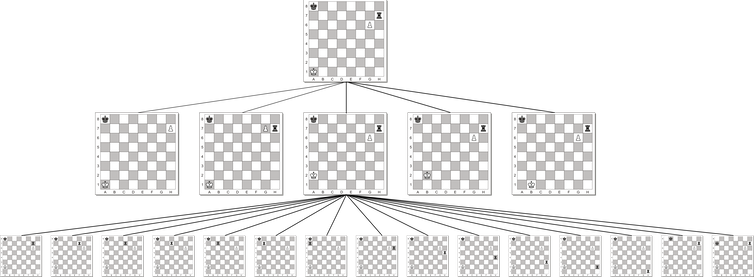

This results in a tree of possible combinations called the search tree. Here’s an example:

An example of a search tree for a particular game.

David Ireland, Author provided

The search tree starts with a root that represents current game play. And the branches are all the possible game plays. Each level of the tree is called a ply, which is a single move by a player.

Deep Blue’s specialised hardware allowed it to search future game play at a staggering 200 million chess positions per second. Even today, most chess AI programs only compute about 5 million positions per second.

Not only does the AI have to search through a large collection of chess positions, but at some stage, it must evaluate them for their potential worth. This is done by a so-called evaluation function.

Deep Blue’s evaluation function was developed by a team of programmers and chess grandmasters who distilled their knowledge of chess into a function that evaluates piece strength, king safety, control of the centre, piece mobility, pawn structure and many other characteristics — everything a novice is taught.

This allows a particular board position to be scored with a single number. Think of the evaluation function as something like this:

How a chess-playing AI evaluates the chessboard.

David Ireland, Author provided

The higher the number, the better the position is for the machine. The machine seeks to maximise this function in its favour, and minimise it for its opponent.

The human

A person, in stark contrast, only considers three to five positions per second, at best. How, then, did Kasparov give Deep Blue a run for its money?

This question has fascinated cognitive scientists who have yet to agree on a computational theory on how even an amateur plays chess.

Nevertheless, there’s been extensive psychological research into the cognitive processes involved in how players of various strengths perceive the chessboard and how they go about selecting a move.

Studies conducted on eye movements of expert players as they select a move showed little consistency with searching a tree of possible moves. People, it seems, pay more attention to squares that contain active attacking and defending pieces and perceive the pieces on the board as groups or chunks rather than as individual pieces.

In an even more revealing experiment, novice and expert players were shown a chess position taken from a game for five seconds. They were then asked to reproduce the board from memory. Expert players were able to reconstruct the board much more accurately than novice players.

Curiously, when they were asked to reconstruct a board that had the pieces randomly distributed, experts did no better than novices.

It is believed that through constant play, a player accumulates a large number of chunks that could be thought of as a language of chess. These chunks were not present with the randomly distributed board and, as such, the experts’ perception was no better than that of the novice.

This language encodes positions, threats, blocks, defences, attacks, forks and the many other complex combinations that arise. It allows players to determine and prioritise pressures on the board and reveal opportunities and dangers.

The language of chess is a higher level of perception of the chessboard that still eludes AI and cognitive science researchers.

Let’s take a look at an interesting position.

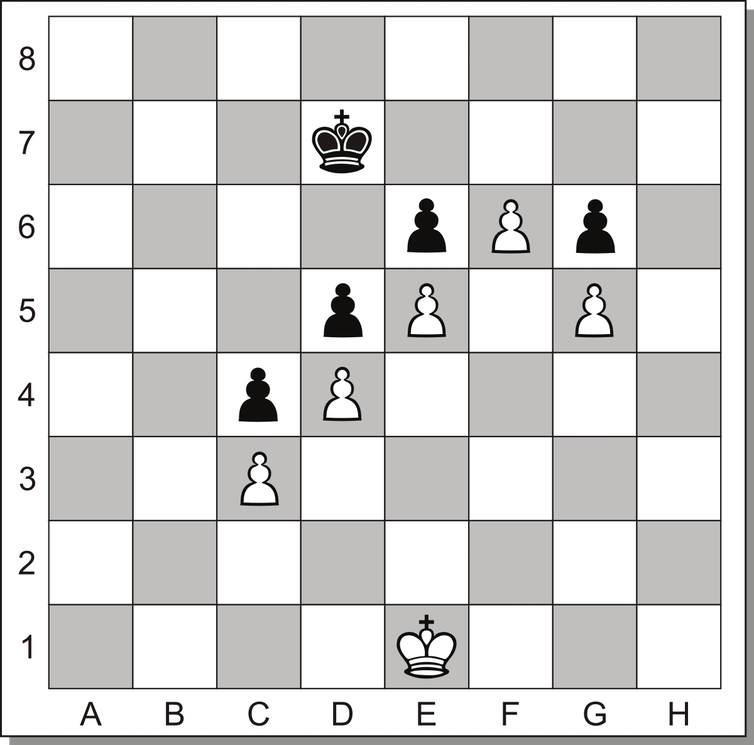

What is white’s winning strategy?

Two kings are on either side of a pawn blockade. White has an opportunity to promote the pawn on F6 to a stronger piece. But that square is being guarded by the black king.

An example problem where human intuition often triumphs over AI.

David Ireland, Author provided

For white to win, the white king must move around the blockade via column A and force the black king away. Defeat for black is then inevitable.

Simple enough? Not entirely for a chess AI, which has more difficulty perceiving white’s advantage. This is because it would need to search to a depth of 20 ply to find white’s advantage. In this position, at 15 plies there are 10,142,484,904,590 possible positions (we tried computing to 20 plies but after one week of computation, we gave up).

Most computer chess programs won’t see the winning strategy. Instead, they will move the white king to the centre of the board which is the common strategy when there are only a few pieces on the board.

Human intuition is still a powerful force.

Higher level of perception

A famous AI researcher, Professor Douglas Hofstader, believes analogy is the core of cognition. We humans, certainly bring our own analogies to the game: gambits, sacrifices, and blockades, among other things.

Alas, research into the field of cognitive science has waned over the past decade in favour of more practical and profitable direct AI approaches as seen in Watson and AlphaGo.

Nevertheless, there has been sporadic research output on so-called cognitive architectures (CHREST) that model human perception, learning, memory, and problem solving.

Some play chess (CHUMP) not by searching for a plethora of combinations but by perceiving patterns and relationships between pieces and squares. And just like most humans, they play mediocre chess.

It’s worth pondering: if true artificial intelligence is established, will it begin with an explosion of intelligence or something smaller and imperceptible?

David Ireland receives funding from Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language.