IQ tests can’t measure it, but ‘cognitive flexibility’ is key to learning and creativity

Einstein thought imagination was crucial. Robert and Talbot Trudeau/Flickr, CC BY-NC

IQ is often hailed as a crucial driver of success, particularly in fields such as science, innovation and technology. In fact, many people have an endless fascination with the IQ scores of famous people. But the truth is that some of the greatest achievements by our species have primarily relied on qualities such as creativity, imagination, curiosity and empathy.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

Many of these traits are embedded in what scientists call “cognitive flexibility” – a skill that enables us to switch between different concepts, or to adapt behaviour to achieve goals in a novel or changing environment. It is essentially about learning to learn and being able to be flexible about the way you learn. This includes changing strategies for optimal decision-making. In our ongoing research, we are trying to work out how people can best boost their cognitive flexibility.

Cognitive flexibility provides us with the ability to see that what we are doing is not leading to success and to make the appropriate changes to achieve it. If you normally take the same route to work, but there are now roadworks on your usual route, what do you do? Some people remain rigid and stick to the original plan, despite the delay. More flexible people adapt to the unexpected event and problem-solve to find a solution.

Cognitive flexibility may have affected how people coped with the pandemic lockdowns, which produced new challenges around work and schooling. Some of us found it easier than others to adapt our routines to do many activities from home. Such flexible people may also have changed these routines from time to time, trying to find better and more varied ways of going about their day. Others, however, struggled and ultimately became more rigid in their thinking. They stuck to the same routine activities, with little flexibility or change.

Huge advantages

Flexible thinking is key to creativity – in other words, the ability to think of new ideas, make novel connections between ideas, and make new inventions. It also supports academic and work skills such as problem solving. That said, unlike working memory – how much you can remember at a certain time – it is largely independent of IQ, or “crystallised intelligence”. For example, many visual artists may be of average intelligence, but highly creative and have produced masterpieces.

Contrary to many people’s beliefs, creativity is also important in science and innovation. For example, we have discovered that entrepreneurs who have created multiple companies are more cognitively flexible than managers of a similar age and IQ.

So does cognitive flexibility make people smarter in a way that isn’t always captured on IQ tests? We know that it leads to better “cold cognition”, which is non-emotional or “rational” thinking, throughout the lifespan. For example, for children it leads to better reading abilities and better school performance.

It can also help protect against a number of biases, such as confirmation bias. That’s because people who are cognitively flexible are better at recognising potential faults in themselves and using strategies to overcome these faults.

Cognitive flexibility is also associated with higher resilience to negative life events, as well as better quality of life in older individuals. It can even be beneficial in emotional and social cognition: studies have shown that cognitive flexibility has a strong link to the ability to understand the emotions, thoughts and intentions of others.

The opposite of cognitive flexibility is cognitive rigidity, which is found in a number of mental health disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder and autism spectrum disorder.

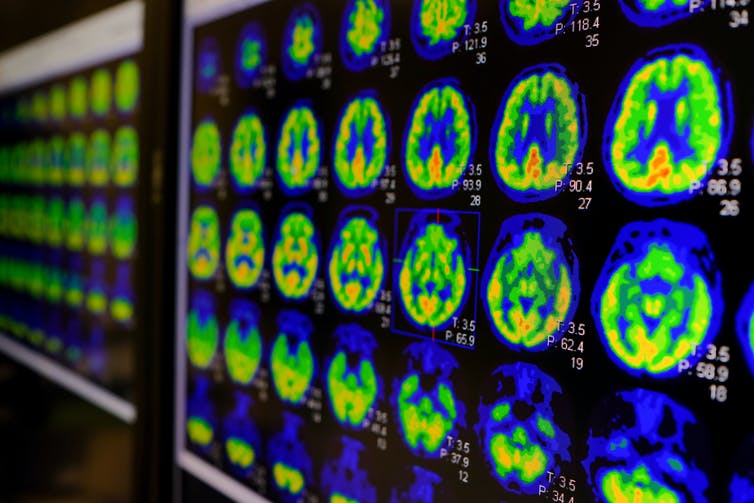

Neuroimaging studies have shown that cognitive flexibility is dependent on a network of frontal and “striatal” brain regions. The frontal regions are associated with higher cognitive processes such as decision-making and problem solving. The striatal regions are instead linked with reward and motivation.

Some people have more flexible brains.

Utthapon wiratepsupon/Shutterstock

There are a number of ways to objectively assess people’s cognitive flexibility, including the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and the CANTAB Intra-Extra Dimensional Set Shift Task.

Boosting flexibility

The good news is that it seems you can train cognitive flexibility. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for example, is an evidence-based psychological therapy which helps people change their patterns of thoughts and behaviour. For example, a person with depression who has not been contacted by a friend in a week may attribute this to the friend no longer liking them. In CBT, the goal is to reconstruct their thinking to consider more flexible options, such as the friend being busy or unable to contact them.

Structure learning – the ability to extract information about the structure of a complex environment and decipher initially incomprehensible streams of sensory information –

is another potential way forward. We know that this type of learning involves similar frontal and striatal brain regions as cognitive flexibility.

In a collaboration between the University of Cambridge and Nanyang Technological University, we are currently working on a “real world” experiment to determine whether structural learning can actually lead to improved cognitive flexibility.

Studies have shown the benefits of training cognitive flexibility, for example in children with autism. After training cognitive flexibility, the children showed not only improved performance on cognitive tasks, but also improved social interaction and communication. In addition, cognitive flexibility training has been shown to be beneficial for children without autism and in older adults.

As we come out of the pandemic, we will need to ensure that in teaching and training new skills, people also learn to be cognitively flexible in their thinking. This will provide them with greater resilience and wellbeing in the future.

Cognitive flexibility is essential for society to flourish. It can help maximise the potential of individuals to create innovative ideas and creative inventions. Ultimately, it is such qualities we need to solve the big challenges of today, including global warming, preservation of the natural world, clean and sustainable energy and food security.

Professors Trevor Robbins, Annabel Chen and Zoe Kourtzi also contributed to this article.

Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian receives funding from the Wellcome Trust, the Leverhulme Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation. Her research is conducted within the NIHR MedTech and In vitro diagnostic Co-operative (MIC) and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Mental Health and Neurodegeneration Themes. She consults for Cambridge Cognition.

The University of Cambridge and Nanyang Technological University Centre for Lifelong Learning and Individualised Cognition (CLIC) research project is funded by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister's Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme.

Christelle Langley is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Victoria Leong receives funding from the Ministry of Education, Singapore and the Centre for Lifelong Learning and Individualised Cognition (CLIC). CLIC is supported by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme.