Millions of young people will head to the polls over the next year – but many are disillusioned about mainstream politics

vesperstock/Shutterstock

A record number of people will go to polls in 2024 to vote in national elections around the world. People who came of age during the last electoral cycle will have an opportunity to cast their votes for the first time.

In wealthier countries with rapidly ageing populations, such as the US and the UK, there will again be record inter-generational divisions in turnout and political preferences.

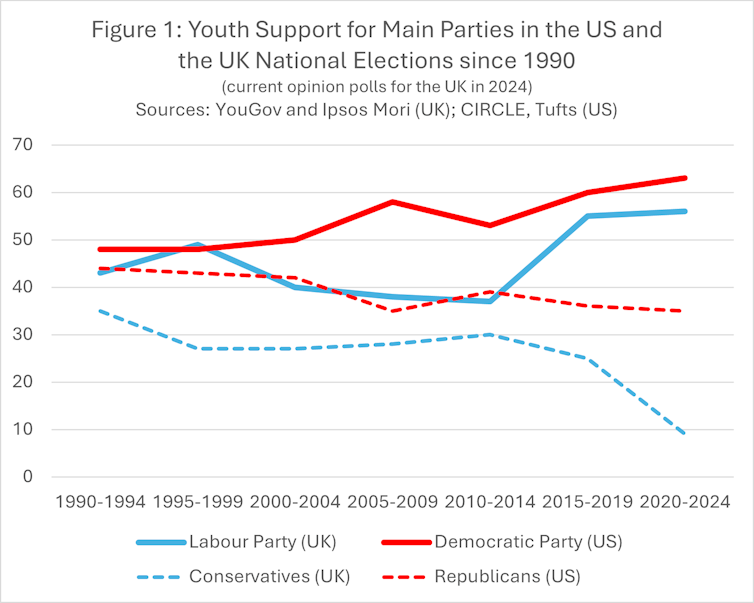

In recent elections, a high proportion of people aged 18–24 supported Democratic party candidates and the Labour party. In 2020, 61% voted for Joe Biden (compared to 37% for Donald Trump) in the US, and 62% voted Labour in the UK’s 2019 general election (compared to 19% for the Conservatives).

Ahead of the UK’s upcoming general election, which could take place as late as January 2025, successive polls have placed the Conservatives at 10% or less among young adults.

Nevertheless, the new generation of young voters in the US and the UK are disillusioned with mainstream electoral politics and are unenthusiastic about casting their votes. In fact, turnout rates for young adults (aged 18–30) are around a third lower than for adults of all ages in these countries.

Youth support for main parties in the US and UK national elections since 1990.

James Sloam, CC BY-NC-SA

Overwhelming youth support for the Democrats and Labour masks a desire for a more radical form of politics that addresses young people’s concerns. Opinion polls often do a poor job of explaining youth priorities across broad categories such as the economy and health. But my own research from 2022 with young Londoners reveals clusters of priorities relating to economic, social and environmental issues.

These issues include housing, personal wellbeing and safety, group rights for women or minorities and broader international questions around climate change and the ongoing situation in Gaza. Compared to older generations, young people are also much more comfortable with diversity in society and much less concerned about immigration.

In the US and the UK, these sentiments were effectively articulated by Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn in recent elections.

Sanders and Corbyn were both viewed by young adults as authentic and radical, believing in what they said, and offering meaningful solutions to pressing problems like low wages, unaffordable housing and university tuition fees. In the 2016 US primaries, Sanders received more votes from young Americans (aged 18–30) than Hilary Clinton and Trump (the two final candidates) put together.

Youth electoral participation (or non-participation) is also defined by a country’s electoral system. In countries with proportional representation, the trend towards socially liberal values and greater state intervention has led to increased support for alternative political parties.

For example, the Green party in Germany became the largest political party among those aged 18–24 at the 2021 federal election. It secured the votes of just under a quarter of young adults – almost as much as the two main parties (Social Democrats and Christian Democrats) combined.

A visualisation of the key political issues identified by young Londoners.

James Sloam, CC BY-NC-SA

Division among the young

Young people are, of course, not all the same. There are important divisions within this age group based on gender, socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

In the UK’s 2017 general election, 73% of young women voted Labour compared to only 52% of young men. And in the 2022 US mid-terms, 71% of young women voted Democrat compared to 53% of young men – a difference that was driven by the 2022 Supreme Court ruling allowing individual states to ban abortion.

In response to the ruling, young women registered to vote in record numbers, casting their ballots against Republican candidates who supported the decision.

These differences are reflected in participation in social movements. For example, the 2019 climate strikes were overwhelmingly comprised of young women and girls. The protests of one girl, Greta Thunberg, in a town square in Sweden, quickly spread into a global movement of millions of young people.

Socioeconomic status plays an equally important role. Young people from poorer backgrounds or with low levels of educational attainment are much less likely to turn out in elections than graduates or young people in full-time education.

In the UK, around two-thirds of university students turned out in recent general elections compared to around one-third of young people from the lowest social group. Young people from low-income backgrounds, if they do turn out, are often drawn to populist right-wing causes, such as the candidacies of Trump in the US and Marine Le Pen in France – especially in the case of young, white men.

The latter point illustrates how race or ethnicity shape youth participation. This is particularly true in the US where an estimated 87% of black youth voted for Biden in 2020 against just 10% for Trump.

However, the support of young minoritised ethnic voters for progressive candidates and parties has proved frustrating, as existential economic and security issues have not been addressed. It was the Black Lives Matter movement and citizen-generated evidence, rather than politicians and parties, that shone a spotlight on police brutality and discrimination in the US and many other countries.

Read more:

Black Lives Matter protests are shaping how people understand racial inequality

The forthcoming elections in the UK, the US and many other rich democracies are likely to be defined by inter-generational cleavages. However, it is far from certain if young people will be drawn to the polls.

There is a dilemma for progressive candidates and parties regarding how far they are willing to go to appeal to younger generations given the inter-generational divisions that exist. Yet this is fast becoming a risk worth taking.

Successive generations of young people are entering the electorate with socially liberal views and positive attitudes towards state intervention to address economic, social and environmental challenges: from poor mental health, to the cost of housing, to concerns about pollution and climate change.

![]()

James Sloam does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.