Only 15 known underwater internet cables connect Australia to the world – and they’re under threat from fishing boats, spies and natural disasters

Undersea Internet cable in Atlantic shore Laiotz/shutterstock

The Australian government this week announced it would spend A$18 million over four years on a new centre aimed at keeping safe the undersea cables that power the nation’s internet.

The Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre is tasked with protecting the critical undersea telecommunications cables throughout the Indo-Pacific region from deliberate interference from malicious actors, or accidental damage.

This is a crucial undertaking. The internet directly contributes $167 billion or more a year to the Australian economy. These cables enable everything from mundane social media updates to the colossal transactions that drive the global economy.

But what is driving Australia’s urgency to better protect these crucial cables now?

The backbone of the internet

Undersea telecommunications cables are laid on the ocean floor at depths down to 8,000 metres. They trace their origins back to the mid-19th century, driven by business interests and the need for imperial control.

The British Empire invested in these cables to connect and control its distant territories. In fact, they were referred to as the “nervous system of the British Empire”.

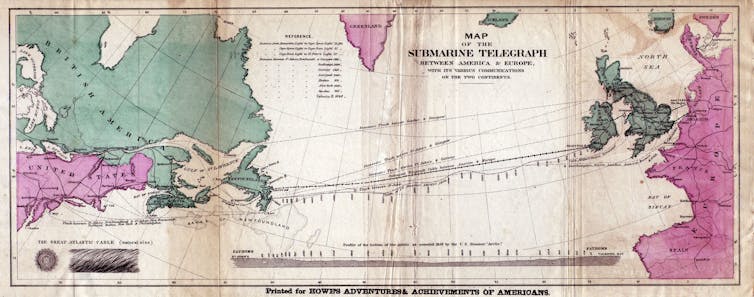

The first transatlantic cable in 1858 demonstrated the potential for rapid communication between continents. This revolutionised business and governance.

Map of the first Transatlantic submarine cable.

Howe’s Adventures & Achievements of Americans/Wikimedia Commons

These cables are typically no wider than a garden hose. They contain optical fibres wrapped in a thick layer of plastic for protection. They can transmit data from one end of the cable to the other at speeds of up to 300 terabits per second.

For context, 20 terabits per second can stream approximately 793,000 ultra-high-definition movies at the same time. With a capacity of 300 terabits per second, the possibilities for handling digital data are virtually limitless.

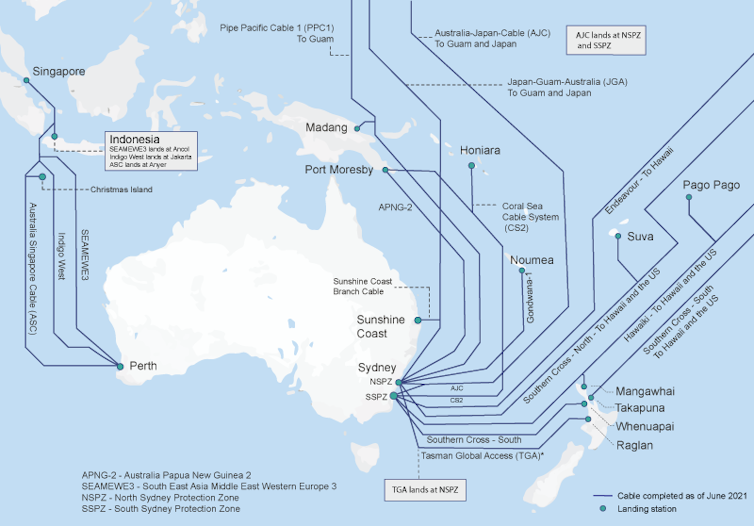

There are currently around 1.4 million kilometres of submarine cables in service globally. Only 15 known international cables manage 99% of Australia’s data traffic.

What will the new centre do?

The new centre will provide technical assistance and training across the Indo-Pacific. It will also support other governments in the region to develop better policy regarding undersea cables.

This continues Australia’s longstanding commitment to protecting undersea cables from threats such as accidental damage by fishing activities or attacks by malicious actors, including both state and non-state entities.

International submarine cables connecting Australia.

ACMA

In 2011, Australia was the first country to join the International Cable Protection Committee (which works to improve the security of undersea cables).

Australia has designated protection zones and stringent regulations for undersea cables. Other countries and industry bodies see this as the gold standard.

Australia has established the new Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre to address vulnerabilities posed by its growing dependency on the internet.

But global techno-political developments have also played a significant part.

New threats

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become the defining feature of the United States-China competition for technological dominance. And we have access to internet based AI tools because of undersea cables.

Breakthroughs in AI also could revolutionise productivity, industry and innovation. AI is already being used in medical research, diagnosis, banking and to streamline workflows. And the defence sector is growing increasingly reliant on AI for data analysis and advanced weaponry.

This further underscores the urgent need for robust data protection – which includes keeping undersea cables safe.

So the new Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre is not merely an economic necessity. It is also crucial to national security. It allows Australia to position itself as a key digital security provider in the region.

Nuance is needed

But the specialised nature of undersea cable technology requires a nuanced approach.

Though staffed by Australian public servants, the new centre’s success hinges on close collaboration with private sector experts experienced in manufacturing, laying and monitoring cables.

This partnership is crucial for addressing physical and digital vulnerabilities, while navigating complex industry and geopolitical dynamics.

The dominance of tech giants such as Google and Amazon is another complicating factor. They control more than 20% of new subsea cable installations in the cable industry.

The government’s new centre must balance national interest with industry control to avoid power concentration. This is particularly crucial as big tech grows more influential.

The government has said the new centre is an important contribution to Quad– a diplomatic partnership between Australia, India, Japan and the US. But the centre will need to engage with other international partners, too.

For example, Australia can learn from countries such as Singapore, which has ambitious cable management strategies. These include plans to double Singapore’s cable network by 2033.

Engaging with countries beyond Quad will also bolster Australia’s digital infrastructure resilience.

A new way forward

The newly announced Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre heralds a shift in Australia’s approach to digital infrastructure security.

Historically, Australia has taken a confrontational stance towards containing Chinese tech. This is exemplified by its 2016 rejection of Huawei’s bid to build the Coral Sea Cable, citing national security concerns.

However, the fact the new centre sits within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade signifies a transition towards a more diplomatic approach.

It reflects Australia’s intent to mitigate China’s influence over subsea infrastructure, AI and technology standards while balancing national security with diplomatic engagement.

Will it work? Only time will tell. But the shift from confrontation to diplomacy is a welcome development. It will likely help Australia navigate an increasingly complex global technological landscape.

![]()

Cynthia Mehboob does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.