The award-winning play that touches hearts and nerves about Cape Town’s history of slavery

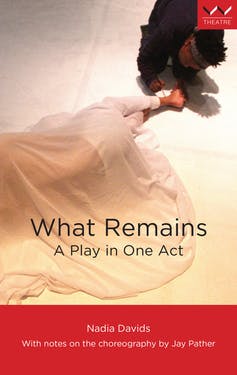

Buhle Ngaba as The Student holds Shaun Oelf as The Dancer. Yazeed Kamaldien/What Remains

What Remains is one of the most successful South African plays of recent years. Written by Nadia Davids and directed and choreographed by Jay Pather, both artists and academics from the University of Cape Town, it has won numerous awards. Most recently Davids received the prestigious English Academy of Southern Africa Olive Schreiner Prize for Drama for the published text. We asked them about creating the work that shines a spotlight on South Africa’s history of enslaved people.

What is the play about?

Nadia Davids: What Remains is a fusion of text, dance and movement that tells a story about the unexpected uncovering of a slave burial ground in Cape Town, the archaeological dig that follows and a city haunted by the memory of slavery. When the bones emerge from the ground, everyone in the city – slave descendants, archaeologists, citizens, property developers – is forced to reckon with a history sometimes remembered, sometimes forgotten.

So the play fictionalises the uncovering of a graveyard at Prestwich Place where, in 2003, a corporate real estate development famously struck an eighteenth century burial ground – one of the largest ever to be unearthed in the southern hemisphere. Nearly 3,000 bodies were accounted for, from babies who were a just few weeks old – the children of enslaved washerwomen – to men in their late sixties.

Four figures – The Archaeologist, The Healer, The Dancer and The Student – move between bones and books, archives and madness, paintings and protest, as they struggle to reconcile the past with the now.

What does it tell us about Cape Town’s history?

Nadia Davids: As I wrote in 2017, “The response in Cape Town was immediate and polarised: the property developers wanted to continue building, heritage managers and archaeologists prioritised a scientific examination of the remains (important data could be drawn from the bones, the material traces held answers, frustrating gaps in archival research could be closed) while an alliance of community activists claiming descendancy from those buried insisted on the immediate reinterment of the bones.

They felt (understandably) that to examine the bones, to pick them over, would be to commit violence afresh on bodies that had in life been subjected to unforgivable cruelty. “Stop robbing the graves!” cried someone at one of the first community meetings, and another, “I went to school at Prestwich Street Primary School. We grew up with haunted places; we lived on haunted ground. We knew there were burial grounds there. My question to the City is, how did this happen?”

It struck me that this discovery – its evidence of terror and the complex response to it – was, in and of itself and a profound metaphor for our country. History, a deeply unresolved history, had literally emerged from the earth and demanded a present-day conversation – and the conversation (or the argument) that came of it was a struggle between capital, memory, hurt, history, the official, the neglected, how we remember and whom we cherish. It was both of its own time and, painfully, of ours.

Why did you ask Jay Pather to collaborate?

Nadia Davids: Jay Pather is a brilliant artist – his choreography is exquisite and captivating but it is also political, deeply felt, impossibly precise, full of a profound understanding of our country and its brutal histories. And yet somehow, it’s always hopeful, dreaming about a different, better future. When I first started writing What Remains I thought I was writing a novella. At a certain point I realised that this was a story that needed liveness, embodiment – collectively, collaboration, immediacy. In other words, it was a play, not a novel. And I knew Jay was the person to direct it.

I approached him with the text and was thrilled that he was interested. Early in our discussions he suggested adding the character of The Dancer. He explained that he wanted to work with movement and dance as a means of understanding the text as “choreographic” in and of itself and that The Dancer’s movement’s would not just animate, but respond to the text and narrate the stories that were unspeakable. I thought this an absolutely electrifying idea.

What did you hope to add with dance, Jay?

Jay Pather: Nadia’s text is pithy – restrained and poetic and yet grounded in major historical events and questions about our future. The dance derives from this, prompted by the text. So dance in the work is not present just as “interludes” and even though there is a designated “dancer” who gives form to all the hauntings, all the actors move. The text moves effortlessly, like seamless choreography, in and out of the ordinary and large scale epochs. Saturated with movement, the direction and choreography follow that cue.

The text pushes the envelope?

Nadia Davids: In the published version, Jay and I were working with the idea of shifting how playtexts are usually created. We wanted to do something genre-bending by including ideas around the staging and evocative descriptions (not steps) of the dance and movement.

What responses have you had from audiences?

Wits University Press

Nadia Davids: Audiences have been deeply invested in the work – people stayed behind to speak to us, they were moved, enraged, disturbed, comforted … In its first iteration in 2016 the play was staged at the University of Cape Town. In 2017 it was invited to the South African National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. Another run in Cape Town followed and then stagings at the 2017 Afrovibes Festival in the Netherlands. Almost all performances were sold out.

Sometimes a work strikes an unexpected chord, is able to articulate a moment or a feeling held by many. In this instance, a simultaneous need for historical reckoning around enslavement, long disenfranchisement and access to the city centre, coupled with a sense – both locally and globally – that we are in a very dangerous moment politically.

The published play is available at Wits University Press

Nadia Davids has received funding from AHRC, The Leverhulme Trust and The Prince Clause Fund. She is affiliated with PEN South Africa.

Jay Pather no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.