The Life And Career Of Hi-Fi Rush Creator John Johanas

The hardest part of being a director is getting out of the car in the morning, John Johanas says. Not literally. He takes the train to work every day. But being a director requires turning a switch in his brain. He’s an introvert. But when he goes to work, he has to be an extrovert. He has to lead teams, micromanage, make tough decisions, and accept making mistakes – all skills he says he learned without clear guidance.

To be able to do that, to make that switch, Johanas says you need to be a “weird psychopath.” Though he likes to think he isn’t a weird psychopath. “Maybe to some people I am,” he says. “I don’t know.” Nevertheless, no one can be at that level all the time. And yet, here he is.

So yeah, the hardest part of the day is getting out of the metaphorical car to go into his job at Tango Gameworks and lead video games, such as The Evil Within 2 and the well-received Hi-Fi Rush. It’s worth mentioning that Johanas had no aspirations of becoming a game developer growing up. Much less a game director in Japan. He was just a kid in Long Island, New York, who liked Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails that moved when he saw an opportunity. Flying by the seat of his pants – making, at least from an outsider’s perspective, some baffling decisions (that, to be fair, paid off in spades) – he ended up here with no choice but to get out of the car and be a director every single day.

Johanas is quoting Stanley Kubrick, who was actually quoting Steven Spielberg during his 1997 acceptance speech for the D.W. Griffith Award when he said (via Far Out Magazine), “I believe Steven summed it up about as profoundly as you can. He thought the most difficult and challenging thing about directing a film was getting out of the car. I’m sure you all know the feeling.”

That said, nearly a decade into his career as a game director, Johanas finally feels a bit confident in his abilities. Not fully. But he’s getting there.

Photo by Alex Van Aken

John Johanas, the director of The Evil Within 2 and Hi-Fi Rush

Talk Show Host

In 2007, the band Nine Inch Nails told Australian fans to steal their music. Singer Trent Reznor was angry their albums cost $30.

“Steal away,” Reznor said on stage at Australia’s Hordern Pavilion (via Wired). “Steal, steal, and steal some more and give it to all your friends and keep on stealing. Because one way or another these mother f—ers will get it through their head that they’re ripping people off and that’s not right.”

Later that year, when the band completed their contract with Interscope Records, they went independent after nearly two decades on record labels. Fans wouldn’t have to steal their music anymore. Nine Inch Nails would give it away for free, as they did with their 2008 album, The Slip. More importantly, they were also giving away the stems (effectively the individual parts that make up a recorded song) so that fans could remix, adapt, and republish their own versions.

“The Slip,” by Nine Inch Nails

Johanas, a fan, sitting in his dorm at Brandies University, downloaded the files, dropped them into GarageBand, and then learned the hard way that he had no technical ability to do anything with the treasure trove of music he had. So, he deleted his work, moved the stems onto a USB – where they’d sit for more than a decade – and moved on.

Johanas was always interested in music growing up. When he was a kid, he played the alto saxophone in his school’s symphonic band. Eventually, he wanted to play a cooler instrument, so he tried guitar. That was too hard, so he picked up bass instead. After a couple of years, he took his lessons and re-applied them to guitar. He then played guitar and sang in a Radiohead cover band. Their standout song, he says, was actually a B-side: “Talk Show Host,” originally featured on the soundtrack for Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet movie.

Radiohead was the band that cracked music open for Johanas; when he realized it isn’t something that just exists. It’s something created. One day in high school, he was with a friend who was also learning guitar, playing a poor rendition of a Radiohead song. Even early as a guitar player, Johanas identified the errors in the player’s strumming patterns. In his head, he realized the song wasn’t all that complex. It only sounded complex. But he could break it down into simple chords going back and forth – the backbone of songwriting. He was dissecting music.

“That removed an illusion for me,” Johanas says. “Because it almost brings it down to a level that’s digestible. You realize, ‘I could do that as well if I put in the effort to learn it. [That] also taught me about that effort that’s involved. You wanna immediately write a song like that, but these people have been playing in a crappy band for ten years, writing nothing that gets released. And then they finally perfect their craft into something. But still, that’s even just a very simple song, but you have to work on it for a long time. I was like, ‘Well, I wanna start working on that.'”

He was also into video games – specifically Japanese games. He got his first chance to see Japan when visiting a friend who had lived in America during their Elementary school years. When she moved back to Japan, their friend group stayed in touch. One year, she floated the idea of everyone visiting her. They all said yes.

But it turned out Johanas was the only one who bought a ticket. He flew out and stayed with her family in Chiba, right outside of Tokyo. Naturally, culture shock smacked him in the face.

Especially coming from New York – with its filthy subway system – Johanas immediately brings up his impressions of the Japanese public transit system (one of the best in the world). He recalls seeing an advertisement for a train that stopped him in his tracks – all because it had one of the Japanese alphabets, Hiragana, on it.

“The Hiragana for ‘no’ [の] I saw that,” he says. “I didn’t even know what it meant. I was like, ‘What is that?!’ They were like, ‘It’s the sound ‘no.’ And I was like, ‘But what does it mean?’ And they’re like, ‘It doesn’t mean anything. It’s a sound.’ I was like, ‘No, it must mean something.’ I don’t know why; it’s the dumbest thing ever. But now you realize it’s just a letter. What does ‘B’ mean? It’d sound the same.”

This is the moment Johanas offers when explaining the earliest steps of how he’d wind up spending more than a third of his life in Japan. He already liked Japanese video games, but now he was also captivated by the country’s visual language – and just the country in general. He wanted to learn more. When he started college, he studied Japanese. He also played drums in a Japanese cover band. One of the bands they covered was called Number Girl.

When he got the chance to study abroad, two options presented themselves: the London School of Economics or going to Kyoto for a semester. In Johanas’ mind, going to London was a safer choice.

“My Dad was like, ‘You should definitely go to that,'” he says.

On the other hand, he’d begun investing much of his life into learning Japanese. What if this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity?

“Everyone else told me, ‘Yeah, but you can, like, probably go there anytime. But you probably won’t get a chance to study abroad in Japan,'” Johanas adds.

He went to Japan.

After a semester, he came home. When he graduated college, he went back to Japan.

He hasn’t left since.

Bottomless Pit

Johanas quickly clarifies that he was not trying to scam anyone into giving him a visa to live in Japan. But that said, he had no desire to be a teacher. But that said, that’s what got him across the border.

Right after college, Johanas started teaching English as part of the JET Program – a government program built to teach foreign languages in Japan and a common way for people to get working visas to move to the country.

Well, he kind of taught English. He taught at two middle schools but was technically an “assistant language teacher.” As he says, the teachers in charge of his classes gave him little to actually do. He had no responsibilities, which for someone in their early 20s was great – at first. Then he realized he wasn’t accomplishing anything. His life had no stakes.

Photo by Alex Van Aken

John Johanas walking around his home in Jiyugaoka in Tokyo, Japan

Johanas landed in Ibaraki, in the mountains north of Tokyo. It was a small town. The only thing open past 8:00 p.m. was a gym that closed at 10:00 p.m. He came to Japan with no game plan other than he’d figure his life out when he got here. He decided he’d spend two years working for JET and outside of work, buckle down on continuing to learn Japanese. He studied Kanji every day. He read and translated Japanese books as language practice. He also, as he puts it, did stupid stuff.

“I ran the Tokyo Marathon,” he says, laughing. “I was like, ‘I’ve never run before; I guess I’ll just train and run the Tokyo Marathon because what else am I gonna do?'”

As his two years at JET came to a close, Johanas realized he didn’t like living in the middle of nowhere. He was from New York. It wasn’t Manhattan, but Long Island was at least close enough to the action. He also worried for his safety out in Ibaraki.

“I still remember driving in the countryside, and it was, like, 8:30 p.m., so it’s not late by any standards, but all the lights were off. Even the streetlights,” Johanas says. “You’re driving through a field. It’s pitch black, and there’s no other cars coming because there’s so few people living there. And if you ever see a Japanese rice field next to a road, it dips off deep […] I was like, ‘If something were to happen, and my car were to drift off the road and fall in this thing, no one would find me, and I’d die.'”

Johanas laughs while telling this story, but it was a helpful deciding factor when planning the next stages of his life. He’d developed a fear of isolation. He had to get out of Ibaraki.

IMAGE SOURCE: TANGO GAMEWORKS

Resident Evil creator and Tango Gameworks founder Shinji Mikami

In March 2010, Shinji Mikami, the creator of, among other things, the Resident Evil series, announced he was starting a new studio in Tokyo after about two decades working in Okaka at companies such as Capcom and PlatinumGames. He called the studio TangoGameworks. Mikami launched Tango with, weirdly enough, a Flash game featuring himself committing harakiri (a form of ritualistic suicide), where the goal was to cut off his head.

More importantly – though equally weird – was Tango’s recruitment page, which, according to Johanas, listed no actual game development credentials.

“It was just like, ‘Likes games, wants to make games,'” he recalls. “I was like, ‘Aight.'”

Johanas grew up playing Japanese and survival horror games. He wasn’t an avid follower, but he was certainly aware of Mikami’s work. Still looking for direction in life, he applied to Tango – and went about it in every incorrect way.

“I did what you don’t do in Japanese – I wrote a cover letter explaining why I applied,” Johanas says. “I got called for an interview, a very casual interview. I also did something that you don’t do in Japanese, which is I called afterward and said, ‘Give me this job. I want this job.’ I don’t know if that was too aggressive or aggressive enough to push me over the edge.”

In his cover letter, Johanas made clear he had no experience. He just loved playing video games. But he’d spent the last couple of years translating Japanese books into English as a hobby. He liked bringing things to a new audience. He thought he could do the same for Tango, bringing the studio’s games to a larger audience. To prove his commitment, he brought a novel he’d translated and gifted it to Mikami, Go by Kaneshiro Kazuki, which at the time had no official translation.

“He gave that as a present to me, which surprised me because it’s like, ‘I don’t even read English,'” Mikami told us back in 2022. “But I saw there was passion in his eyes.”

Whether or not Johanas had experience or had been too aggressive in his application, it didn’t matter. He got the job, becoming one of the earliest Tango employees. He was moving to Tokyo.

He was a Japanese game developer now.

Head Down

When Mikami announced Tango, he made his mission statement clear: give young directors a chance to lead their first video game. As he told Polygon at the time, there were too many people older than 40 heading projects.

By most measures, he made good on this before leaving the company in 2023, but he did have to take the reins for the studio’s first project, The Evil Within (though that was more a function of needing funding than anything else).

Tango Gameworks: A Decade Years Later

Back in 2022, we talked to a number of directors and producers at Tango Gameworks – including founder Shinji Mikami and Ghostwire: Tokyo director Kinji Kimura – about the company’s mission statement more than a decade into its history. Read more here at the link.

But just because people now had chances doesn’t mean they had guidance.

“We were left to our own devices,” Johanas says. “That’s kind of important, but I also can see how that’s a criticism. It’s like a learn-by-doing, learn-by-watching thing.”

Interestingly, Johanas was not hired as a translator but as a level designer. Of course, he had no experience, and it wasn’t like anyone was sitting him down and showing him the fundamentals. As he puts it, there was no “Tango Education Program.” So, he got to work teaching himself parts of the job.

Early in Tango’s history, Zenimax, the owner of Bethesda Softworks, acquired it, leaning on Mikami’s pedigree as a horror developer. The studio made The Evil Within using id Tech 5, id Software’s internal engine, then also used for the 2011 game Rage. Tango had access to Rage’s in-game assets, allowing Johanas to experiment quickly with how level design actually works. He made simple stuff, like trying to get doors to open or original Doom levels using Rage’s assets (this was before the 2016 Doom reboot). He was gradually putting the pieces together for how he’d have to make levels in this video game he’d found himself working on.

A lot of his early work probably wasn’t very good. But as he realized back in high school dissecting Radiohead songs, with enough work and iteration, as he puts it, his 80th level might be.

On The Evil Within, Tango gave level designers free rein over their assignments. Johanas was in charge of a level set inside a mansion, which was basically his only direction. “It was like, ‘Okay, you’re going to go to this mansion level. This is the home of the villain Ruvik, and you’re going to learn about him. That’s it,'” he says. “‘Figure it out.'” It was a story-driven level, but the story changed a lot during development, so the level also had to change a lot, too.

Johanas calls the early days of Tango “freestyle.” There was little overall structure. It was also going through the natural growing pains of any new studio; there were culture clashes as people from other companies came on board with their own methods of doing things. Johanas thinks Tango retained some of the Capcom spirit, considering many of its employees had previously worked there. He describes it as a “seat of your pants” approach – less “200-page” documents detailing how game features will work and more putting things in the game and seeing if they work. He thinks that approach is better, but not without its faults. While he likes the ability to do whatever you want, when you were looking for that structure at Tango, it wasn’t there.

But an advantage to that came after The Evil Within was released in 2014, when Johanas, a complete junior at the studio, made his pitch for the game’s DLC.

The Evil Within

He was frustrated by the game’s story. It didn’t make sense. Or, as he puts it, “Messy is a nice way of saying it.” He came up with a pitch document with ideas for gameplay without firearms and thoughts on ways to fill in plotholes from the main game. You’d follow the character Juli Kidman through the events of The Evil Within, explaining the situations protagonist Sebastian Castellanos had found himself in. He didn’t think he’d lead the project. He just had some ideas.

Mikami might’ve directed The Evil Within, but it was time to give someone else a chance: with no previous experience, Johanas was now in charge of the game’s two DLCs, The Assignment and The Consequence. Like level design before it, he had to learn through experience.

“It was a fun-yet-traumatic period,” he says. “Because you’re obviously doing a lot of stuff that you don’t know, and you’re making lots of mistakes. People are supporting you. People are not supporting you because you’re inexperienced. You have to fight for some things. You lose a lot of battles.”

Becoming a director meant learning you have to be the person with answers – for everything. Creative decisions. Key art. Assets. You name it. Whatever it is, you just need to have an answer. And inevitably, you’re not going to always get it right. “Then you have to understand the humility of saying, ‘I was wrong, I’m sorry,” Johanas says. “‘I’m sorry you wasted your time.'”

The Evil Within: The Assignment

He wasn’t sure he’d ever get the chance to be a director again, so he went all out. It was stressful but also fun. He recalls times the team was struggling. The solution was somtimes to get drunk, eat pizza, come up with “crazy ideas,” put them in the game, and see what works. The project was small enough that there was that flexibility. Again, there was no guidance. Someone might come in and offer some advice if you’re struggling or things are going wrong, but other than that, as Johanas tells it, Tango was operating under the principle: “Be confident. Do your way.”

For the DLCs’ stories, Johanas leaned on his only writing experience: a script writing class he took in college. That’s when he learned he had to write what he knew. In The Assignment, Kidman’s in a situation where she’s given way too much responsibility and, as Johanas puts it, chased by her boss, who has way too much clout.

“Well, it’s funny because in The Consequence,” he continues, “she basically usurps her boss. Literally, like, kills a mental image to become in charge of herself.”

We Never Sleep

Johanas was the director of The Evil Within 2. He didn’t have a choice. He was told. It was daunting.

“It was that thing where I was like, ‘Alright, so for the next x-years, I will have no life outside of this,'” Johanas says. “It’s that weird mental preparation because you have to be thinking about it all the time, in a sense.”

From the jump, Johanas knew he had his work cut out for him; he knew how big and complicated full games were to develop. Sure, he’d directed the DLCs and led his level on the first game, but directing an entire game – a sequel, no less – comes with its own challenges. There are player expectations, things you must improve versus keeping the same, and any number of minute decisions. Johanas also had to learn how to lead a project and team at that scale.

The Evil Within 2

He says Mikami is good about seeing where things are going wrong and offering advice when possible. But as you might imagine, even though Johanas was embarking on this massive undertaking, he was doing it with a lack of guidance or mentorship from Mikami – then the director at Tango with the most experience.

“It was kind of non-mentorship in that sense,” Johanas says. “It wasn’t like, ‘Let’s meet every Friday. Let’s talk about what you’re thinking.’ It wasn’t like a therapy session. There would be weeks, months, or something like that where we’d not speak. And then he’d be like, ‘Hey, what the f—‘s happening?'”

In 2022, when speaking with Tango producer Masato Kimura, he echoed this sentiment: “Mikiami-san makes a mindful choice to kind of stay in the background, a couple steps behind, to watch over things.”

Johanas has nothing negative to say about Mikami as a person in any sense – the opposite, in fact – but still, the expectation that he might be more hands-on with his new directors was not the case, at least not for Johanas. Was that hands-off approach a good or bad thing?

“I don’t know,” Johanas says. “I don’t know, because you have a certain vision, you wanna go with it. There’s a lot of risks, obviously, when you work on a big project. These aren’t cheap things to make; you’re using other people’s money; you have to deliver a good product to people. It would be irresponsible to not mentor some people. But I think that mentorship should probably depend on what you see that person’s capable of doing if they need that. I’d like to think that either it didn’t seem as necessary [for me] as other things, or maybe that was sort of the trial by fire.”

Because The Evil Within 2 was a sequel, Johanas, without divulging specifics, says the game’s development timeline was much shorter than the first game. That said, from the jump, as expected, the team wanted to push for a bigger, better, and certainly prettier product. And maybe it pushed too much, as far as Johanas is concerned. With more than five years behind him and The Evil Within 2’s release in 2017, when asked to reflect on the project, he admits it wasn’t a positive experience.

Photo by Alex Van Aken

John Johanas

It’s not to say he doesn’t like the game. He says he’s always impressed by what Tango can accomplish, even within short timetables. But the massive amount of work took its toll. He says he thought he was prepared. He wasn’t.

“I actually have a weird blackout because I was doing so much work,” Johanas says. “Trauma from how much involvement you had to [put] in there.”

When people ask him if he remembers certain things during development, he sometimes doesn’t. He attributes the memory gaps to the stresses of the time, an experience he says he doesn’t like to look back at. When the team finished the project, he worried other people would feel the same. “Naturally, that’s just difficult for anyone,” Johanas says.

“I’m not ashamed of the game by any means,” he continues. “I’m actually very proud of it. But there are things you realize, ‘We need to do better next time.’ Or, ‘I need to do better next time.’ That directly informed how I went about pitching and making and producing the next game.”

I’ve Seen Footage

When Johanas talks about the bands he’s been listening to lately, a common theme runs throughout.

Violence. Both artistic and literal.

He’s been listening to Death Grips, a rap group known for their harsh, somewhat-unlistenable music, unpredictable live shows, and antagonistic relationships with just about everyone. “They hate themselves, and they hate their fans,” Johanas says, laughing. Infamously, during a dispute with their label Epic Records over the release of 2012’s No Love Deep Web, Death Grips leaked the album, prompting the label to drop them. The album got over 34 million downloads on BitTorrent, so who’s really to say who won that fight?

Photo by Kenny Sun (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Death Grips performing in NYC

Johanas is also a fan of Boredoms, a noise rock band founded by Yamantaka Eye, perhaps most famous for driving a bulldozer through a venue, which he then used to chase the audience before nearly burning the place down with a Molotov cocktail. There were also the shows where he chopped a dead cat in half on stage and threw it at the audience, nearly cut his own leg off, and a number of other ridiculous things. But that was in his wilder days fronting the band Hanatarash. Boredoms are much more mellow, as evidenced by when Johanas saw Eye break his ankle mid-performance and have to be held up the rest of the show.

Okay, maybe not.

“It was a different version, but equally as violent,” Johanas says.

His music choices might explain a game like, say, The Evil Within 2 with all its blood and gore. But his most recent game is, in fact, a music game. However, Hi-Fi Rush couldn’t be further from Johanas’ recently-played artists. For one, it’s colorful, bright, and funny. And Johanas didn’t nearly cut his own leg off during its development.

From the jump, Hi-Fi Rush was a departure for Tango, a far cry from its growing horror catalog. In fact, Mikami had turned down horror projects in the years before founding the studio. He didn’t want Tango to only be a horror developer – its first two unreleased projects were actually a joke game about a cockroach who shot a gun and a canceled open-world sci-fi project inspired by Dune called Noah. Mikami went so far as to tell us in 2022 about The Evil Within that “at the time, yeah, if there was a chance not to work on a horror game, then maybe I would’ve considered that.” But by this point, it had developed multiple survival horror games and had the spooky Ghostwire: Tokyo in development. After The Evil Within 2, Johanas felt it was time to move.

“Me, sitting in the back row, coming off this project, and seeing people move on a theoretical conveyor belt to get further and deeper in there, I was like, ‘If we’re going to do it, we gotta do it now,'” he says.

The roots of Hi-Fi Rush go all the way back to The Evil Within when Johanas had an idea for an action game played to the rhythm of the game’s soundtrack. He used to mention it casually around the office to coworkers. It seemed like a fun idea, like seeing a movie trailer perfectly synced with music. He wanted to make a game that had that same impact.

But it would be a tough sell for Tango. To pull it off, his pitch needed to be ironclad. He needed to prove it could work before anyone had even said yes. So Johanas and one other person, Tango lead programmer Yuji Nakamura, took a year to start building prototypes, learn Unreal, and prepare their pitch for Hi-Fi Rush.

The first prototype tested early gameplay ideas. The first proof of concept was made to test licensed songs. Johanas had an idea about how to structure levels around music so that phases of a boss fight could transition with the different parts of a song. This was, of course, too early in the process for Tango to have actually licensed any music yet, but the team needed stems to test their ideas.

“And I was like, ‘I got something,'” Johanas says.

Those Nine Inch Nails stems saved onto a USB more than a decade earlier finally came in handy; the song “1,000,000,” which is in the game, became the proving ground that Johanas’ licensed music idea could – and did – work.

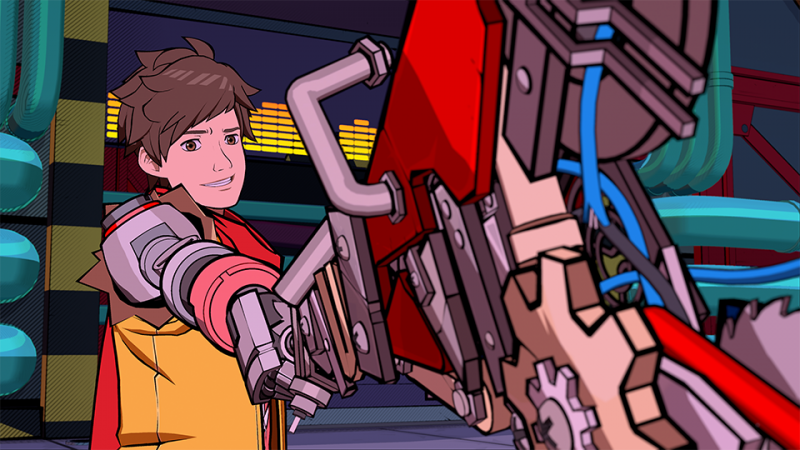

Hi-Fi Rush

Around the office, Hi-Fi Rush gained traction, and its team size grew. It was, of course, unlike anything Tango had made or was making at the time. The very concept was ridiculous: you play as a music-obsessed 25-year-old named Chai with an mp3 player in his chest. Everything – from the combat to the actual world – moves to the beat of the music.

“Internally, it became this viral thing,” Johanas remembers. “It was funny. Like, people didn’t know we made it. It was just passed around. And then when it was later announced that we were making it, they were like, ‘What?'”

But even if Tango was onboard, Johanas knew he still had an uphill climb in front of him. First off, there were the studio’s fans. He felt there would be pushback because this new game wasn’t The Evil Within 3. There was also Tango’s publisher, Bethesda, known mostly for gritty, first-person shooters like the Fallout series. He became obsessive.

“Internally, it was almost like a disgusting level of commitment to our product,” Johanas says.

“It was like, ‘Everything that we show needs to be flawless,'” he continues. “Because there’s a million reasons why they could theoretically cancel this project. It’s weird. It’s out there. It’s not Bethesda. ‘You guys didn’t pull it off. We had confidence at first. We don’t have confidence now.’ I was like, ‘We need to hit every milestone perfectly and impress everyone even further than the last one.'”

A producer at Bethesda did a lot of the legwork getting the publisher onboard, sending a demo first to the company’s younger employees. As Johanas recalls, the different tone struck a chord. They’d come back claiming they’d played the 10-minute demo 15 times.

“Then it became like a rumor. It’s like, ‘Yo, I heard you got this thing. Can you get me in on that?'” Johanas says. “I still remember at some meeting, I think it was still early, and Todd Howard [director on the Fallout and Elder Scrolls series] was there. He was like, ‘I heard about this thing that you’re making. When can I get an invite to this thing?’ I was like, ‘I dunno.'”

Eventually, Bethesda gave the green light. Johanas had made the hard sell. Hi-Fi Rush was going to come out.

Everything In Its Right Place

In Hi-Fi Rush, your central thrust is taking down the bosses of various departments within a corrupt megacorporation. There’s the CEO, the head of marketing, finance, and so on. The game’s bosses are literal bosses.

Johanas works at a company. One owned by a billion-dollar corporation, no less, that during the development of Hi-Fi Rush was bought by Microsoft, a trillion-dollar company. He again leaned on writing what he knew.

“Once you’re in a big business, and not to throw shade at anyone in Bethesda or Microsoft, you realize that these are human people who don’t get along a lot of times and who argue,” Johanas says. “It’s kind of a cluster-f–k that things miraculously happen.”

His story became a satire of the corporate life he was actually living to a degree. People love to think that giant corporations are these well-oiled machines all running some global conspiracy with the government or something ridiculous to that effect. From his perspective, he doesn’t buy it.

“I can’t get people to show up to a meeting,” he says. “Let alone plan a worldwide conspiracy theory that doesn’t leave any sort of paper trail whatsoever. Impossible!”

Hi-Fi Rush

Luckily, the corporations above him were behind his weirdo idea. And they could help with music licensing – unknown territory for Tango and, as Johanas calls it, “the biggest pain in the ass.”

On top of the game’s original soundtrack, Tango licensed music from Nine Inch Nails, The Prodigy, The Joy Formidable, and others. It even got a Number Girl song in there for good measure.

That said, while he won’t divulge who, some artists said no. And even artists that ultimately said yes were hesitant. Licensing music is hard.

“We were not just going into regular licensed music; we were going into this deep level of, ‘We want to use your music. We need the stems. We’re going to remix it, but we’re calling them authentic remixes because we don’t want to take your song and ruin it. It’s like a tribute to your song,'” Johanas says. “But we also were very secretive about the project. So it’s like, ‘We can’t really show you what we’re doing.’ And in certain cases, we actually did.”

“I wanna say Billy Corgan [of the Smashing Pumpkins and Zwan, the latter of which is in Hi-Fi Rush] wanted to see it,” he adds.”

Hi-Fi Rush was initially supposed to be teased in 2020, a plan the ongoing pandemic ruined, but was instead surprise-launched in 2023 on Xbox and PC during a Bethesda livestream. Any apprehensions the team might’ve had about the release model dissipated when reactions started rolling in.

Hi-Fi Rush was, more or less, a hit for the studio. At least in terms of reception – there’s some disagreement over its financial success (it’s worth pointing out the game was also released on Xbox for Game Pass subscribers). Nevertheless, it’s built a large fandom compared to other Tango games, further boosting the company’s profile. Johanas has also spent the months since its release doing dozens of interviews promoting the game. He spends a lot of time replying to fans on Twitter, too, thanking them for playing. Most recently, Hi-Fi Rush won Best Original IP at the annual Develop Conference Awards.

Want More Tango?

To read more about the people of Tango Gameworks – both past and present – check out our previous features.

Last summer, we toured the hidden alleys and sidestreets of Tokyo’s Shibuya ward with Ghostwire: Tokyo producer and director Masato and Kinji Kimura, respectively, learning how the area influenced their game.

We’ve also written extensively about former Tango director Ikumi Nakamura, including a profile on her life and career, as well as a piece where we explored Tokyo late at night, long after everyone had gone to bed.

It has its detractors, sure. People still tweet at Johanas every day about The Evil Within 3. Or they discount Hi-Fi Rush because of its comic book art style. Or they think Tango didn’t have confidence in it because of the stealth drop. Or they see the $30 price point on Xbox and PC as a mark of a lesser game. But for the people who connect with Hi-Fi Rush, they really seem to click – art style, pricepoint, and whatever else be damned.

“I think you see it in the Steam comments; it’s like, ‘Why is this game $30? There’s more content in this than an Uncharted game,'” Johanas jokes.

But the biggest takeaway was gaining the further support of his team. He recalls a story Mikami told him.

“When he made Resident Evil, he was making this game that he thought was good,” Johanas says. “When they were doing the final check, one of the team members who was checking the final version of the game, he goes to Mikami-san, he’s like, ‘This is actually pretty cool!’

“And he’s like, ‘You were working on this game the whole time, and you didn’t think it was good?’ He’s like, ‘Holy crap.’ That was a moment for him where he realized, ‘People were just lying to me the entire time.’ Realistically, that is true. Not everyone can see the goal. Not everyone can see the finish line. They’re hiding their nervousness a lot of the time.”

“The [best] thing about releasing something that is well-received is the community of people who you make a game with, your team, becomes more supportive,” he says. “[They’re interested in] taking the jump with you. Through the whole project, I was totally understandable of everyone freaking out about, ‘Is this going to work? I don’t get it.’ But I was like, ‘Please, just trust me on this one.’ Especially when it was coming together at the end, all the pieces coming into place, we were hitting those benchmarks. The team were like, ‘This is really good.'”

Photo by Alex Van Aken

John Johanas walking around his home in Jiyugaoka in Tokyo, Japan

Whirring

In his D.W. Griffith Award speech, Kubrick went on to talk about the joys of film-making (while also conveniently side-stepping addressing Griffith’s racist views and films, instead comparing him to the myth of Icarus and calling him an artist that took “tremendous risks,” but that’s beside the point).

He said: “Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film also knows that although it can be like trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car in an amusement park. When you finally get it right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.”

Johanas is finally starting to feel confident as a director. Not entirely; he says no one’s ever fully confident. But he’s getting better at trusting his instincts, learning from experience, and knowing how to better prepare for new projects.

He never planned to be a game developer. He definitely never planned to be a game director. Hell, he says he didn’t even see himself being in Japan at one point – much less having spent more than a third of his time on Earth there, fluent in the language (his thoughts are in both English and Japanese now, if you’re curious), and having built a life for himself. Maybe one day he’ll leave. Maybe he won’t. He says he just goes with whatever feels right.

For now, with several games under his belt, being a director still feels right. And maybe no other joys can equal that feeling for him.

When we wrap up the interview, although it’s long into the afternoon, Johanas says he’s going to the office to work.

It’s still a new day, after all. He has to get out of the car.

This article originally appeared in Issue 358 of Game Informer.