The power of rewards and why we seek them out

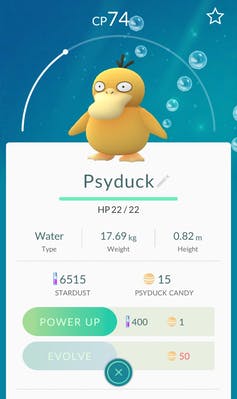

Games like Pokémon GO cleverly exploit our psychology in the way they dole our rewards to keep players hooked. Shutterstock

Any dog owner will tell you that we can use a food reward as a motivation to change a dog’s behaviour. But humans are just as susceptible to rewards too.

When we get a reward, special pathways in our brain become activated. Not only does this feel good, but the activation also leads us to seek out more rewarding stimuli.

Humans show these neurological responses to many types of rewards, including food, social contact, music and even self-affirmation.

But there is more to reward than physiology: differences in how often and when we get rewarded can also have a big impact on our experience of reward. In turn, this influences the likelihood that we will engage in that activity again. Psychologists describe these as schedules of reinforcement.

It’s not (just) what you do, it’s when you do it

The simplest type of reinforcement is continuous reinforcement, where a behaviour is rewarded every time it occurs. Continuous reinforcement is a particularly good way to train a new behaviour.

But intermittent reinforcement is the strongest way to maintain a behaviour. In intermittent reinforcement, the reward is delivered after some of the behaviours, but not all of the behaviours.

There are four main intermittent schedules of reinforcement, and some of these are more powerful than others.

Fixed Ratio

In the Fixed Ratio schedule of reinforcement, a specific number of actions must occur before the behaviour is rewarded. For example, your local coffee shop tells you that after you stamp your card nine times, your tenth drink is free.

Fixed Interval

Similarly, in the Fixed Interval schedule, a specific time must pass before the behaviour is rewarded. It is easy to think about this schedule in terms of work paid on an hourly basis – you are rewarded with money for every 60 minutes of work you complete.

Variable Ratio

For the Variable Ratio schedule, rewards are given after a varying number of behaviours – sometimes after four, sometimes five and other times 20 – making the reward more unpredictable.

This principle can be seen in poker (slot) machine gambling. The machine has an average win ratio, but that doesn’t guarantee a consistent rate of reward, so players continue in the hope that the next press of the button is the one that pays off.

Variable Interval

The Variable Interval schedule works on the same unpredictable principle, but in terms of time. So rewards are given after varying intervals of time – sometimes five minutes, sometimes 30 and sometimes after a longer period. So at work, when your boss drops in at random points of the day, your hard work is reinforced.

It is easy to see that rewards given on a variable ratio would reinforce behaviours far more effectively – if you don’t know when you will be rewarded, you continue to act, just in case!

Psychologists describe this persistent behaviour as a resistance to extinction. Even after the reward is completely taken away, the behaviour will remain for a while because you aren’t sure if this is just a longer interval before the reward than usual.

We all respond to rewards, but only if they are rewarding enough.

Keith Williamson/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Do rewards have a ‘dark side’?

You can certainly use these principles to shape someone’s behaviour. Loyalty cards for supermarkets, airlines, and restaurants all increase the likelihood of our continued use of those services.

Marketers can also use reward to their advantage. If you can make someone feel anxious because they don’t own a particular product – maybe the latest or greatest version of something they already have – when the person buys the new product, the reward comes from the reduction in anxiety.

Want more help around the house? Start off with praising your partner/kids every time they do the desired behaviour, and once they are doing it regularly, slip into a comfortable variable ratio mode.

And of course, sometimes rewards can result in addiction.

Addiction used to be seen in the context of substance use, and there is indeed substantial evidence for the role of reward pathways in alcohol and other drug addiction.

Obviously, the nature of addiction is complex. But more recently, there is evidence of addiction that can be based on behaviour, rather than ingesting a substance.

For example, people show addiction-like behaviours related to their mobile phone use, shopping and even love relationships.

Pokémon GO rewards

Recently the world has watched the introduction of the mobile game Pokémon GO. Cleverly, this game employs multiple schedules of reinforcement which ensure users continue to feel the need to “catch ‘em all”.

On the fixed ratio schedule, users know that if they catch enough Pokemon they will level up, or possess enough candy to evolve. The hatching of eggs also follows a fixed interval, in this case it’s distance walked.

Discovering a rare Pokémon can keep players hooked.

But on the variable ratio and interval schedules, users never know how far they need to wander before they will find a new Pokemon, or how long it will be before something other than a wild Pidgey appears!

So they continue to check the app regularly throughout the day. No wonder Pokemon GO is so addictive.

But it’s not just Pokemon masters who fall prey to online reward schedules.

Checking our emails at various points of the day is reinforced when there is something in our inbox – a variable interval schedule. This makes us more likely to check for emails again.

Our social media posts are reinforced with “likes” on an variable ratio schedule. You may be rewarded with likes on most posts (continuous reinforcement), but occasionally (and importantly, unpredictably) a post will be rewarded with much more attention than other posts, which encourages more posting in the future.

Now, if you will excuse us, we just need to click “refresh” on our inbox. Again.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.