Want your kids to learn another language? Teach them code

Coding: it's just another language to learn at school. Flickrabg_colegio, CC BY

Among Malcolm Turnbull’s first words as the newly elected leader of the Liberal Party, and hence heading for the Prime Minister’s job, were: “The Australia of the future has to be a nation that is agile, that is innovative, that is creative.”

And near the heart of the matter is the code literacy movement. This is a movement to introduce all school children to the concepts of coding computers, starting in primary school.

One full year after the computing curriculum was introduced by the UK government, a survey there found that six out of ten parents want their kids to learn a computer language instead of French.

The language of code

The language comparison is interesting because computer languages are first and foremost, languages. They are analogous to the written versions of human languages but simpler, requiring expressions without ambiguity.

They have a defining grammar. They come with equivalent dictionaries of nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs; with prepositions and phrase patterns, conjunctions, conditionals and clauses. Of course the dictionaries are less extensive than those of human languages, but the pattern rendering nature of the grammars have much the same purpose.

Kids that code gain a good appreciation of computational thinking and logical thought, that helps them develop good critical thinking skills. I’ve sometimes heard the term “language lawyer” used as a euphemism for a pedantic programmer. Code literacy is good for their life skills kit, never mind their career prospects.

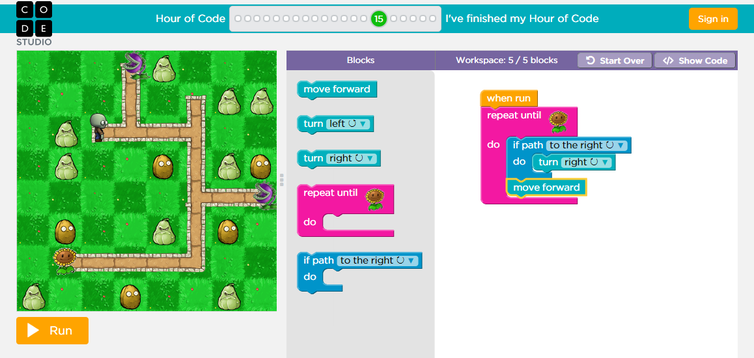

Scratch is one of a new generation of block programming languages aimed at teaching novices and kids as young as eight or nine to write code.

Scratch teaches code with movable instruction blocks.

Screenshot from code.org

The Scratch language uses coloured blocks to represent the set of language constructs in its grammar. A novice programmer can build up a new program by dragging-and-dropping from a palette of these blocks onto a blank canvas or workspace.

The individual shapes of the blocks are puzzle-like, such that only certain pieces can interlock. This visually enforces the grammar, allowing the coder to concentrate on the creativeness of their whole program.

The Scratch language (and its derivatives) are embedded in a number of different tools and websites, each dedicated to a particular niche of novice programmers. The code.org website is a prime example and has a series of exercises using the block language to teach the fundamentals of computer science.

Code.org is a non-profit used by 6 million students, 43% of whom are female. It runs the Hour of Code events each year, a global effort to get novices to try to do at least an hour of code.

For a week in May this year, Microsoft Australia partnered with Code.org to run the #WeSpeakCode event, teaching coding to more than 7,000 young Australians. My local primary school in Belgrave South in Victoria is using Code.org successfully with grade 5 and 6 students.

Unlike prose in a human language, computer programs are most often interactive. In the screenshot of the Scratch example (above) it has graphics from the popular Plants vs Zombies game, one that most kids have already played. They get to program some basic mechanics of what looks a little like the game.

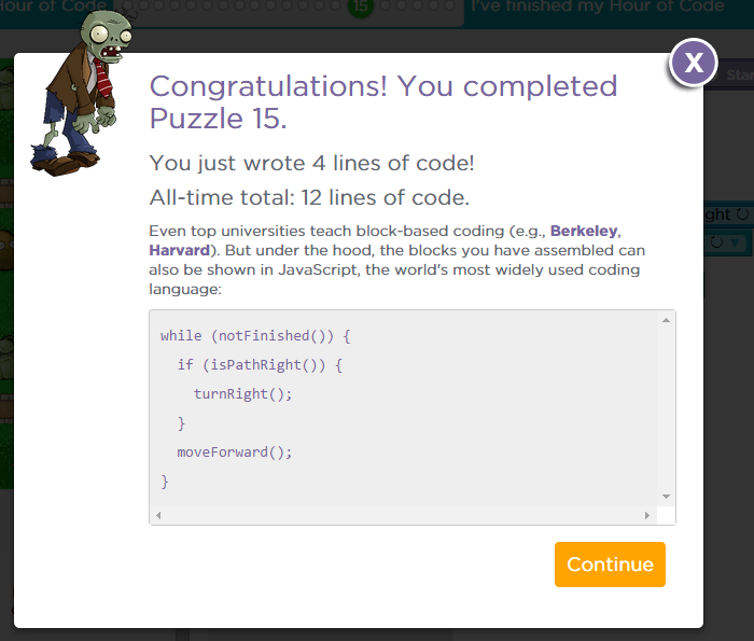

Hit the ‘Show Code’ button at it reveals the JavaScript language behind the coloured blocks.

Screenshot from code.org

But code.org has a ‘Show Code’ button that reveals the JavaScript code generated behind the coloured blocks (see above). This shows novices what they created in tiles, translated into the formal syntax of a programming language widely used in industry.

It’s not all about the ICT industry

Both parents and politicians with an eye to the future see the best jobs as the creative ones. Digging up rocks, importing, consuming and servicing is not all that should be done in a forward-thinking nation.

But teaching kids to code is not all about careers in computer programming, science and software engineering. Introducing young minds to the process of instructing a computer allows them to go from “I swiped this” to “I made this”. From watching YouTube stars, to showing schoolyard peers how they made their pet cat photo meow.

It opens up young minds to the creative aspects of programming. Not only widening the possible cohort who may well study computer science or some other information and communications technology (ICT) professions, but also in design and the creative arts, and other fields of endeavour yet to transpire or be disrupted.

For most kids, teaching them to code is about opening their mind to a means to an end, not necessarily the end in itself.

Steve Goschnick has received research funding from the Australian Research Council, Ericsson Australia Ltd (1998-2000), The University of Melbourne, and a Telstra Broadband Development Grant (2004). He has been the Managing Director of Solid Software Pty Ltd, a data modelling and software development consultancy, since 1998.