Why Google wants to think more like you and less like a machine

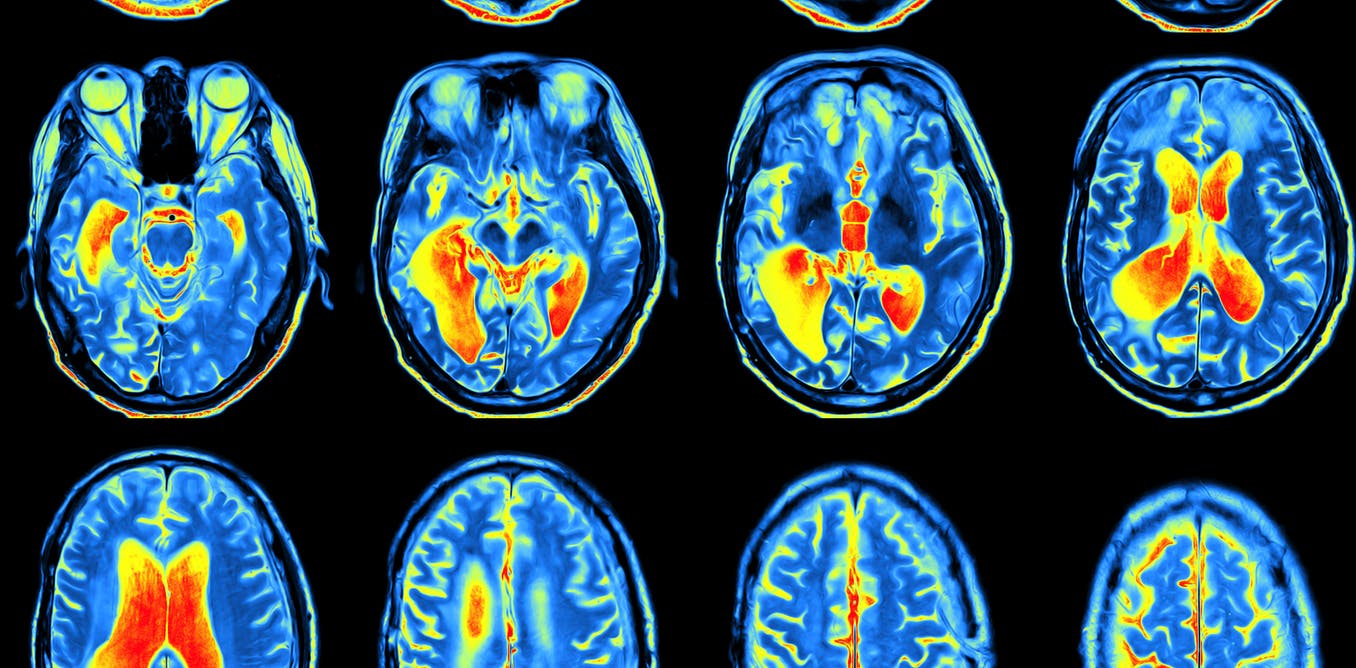

All those neurones: if only a machine could really think like a human. MriMan/shutterstock

What does this mean:

wht has Don Trm don nw?

You’ve probably decided the intended question is: “What has Donald Trump done now?”

But how did you reach that conclusion? The word fragments could be part of many different words. You even expanded two almost identical fragments – “Don” and “don” – to different words – “Donald” and “done”.

When you enter those partial words into a Google search, none of the top search results relate to the current President of the United States.

No mention of Donald Trump in the search results.

Google search/screenshot

So Google’s not that smart after all. Clearly, its search programmers and engineers need to better understand what is going on in the human brain if they are to improve their search engine algorithms. And that’s why they’re turning to neuroscientists for help.

Read more:

Terminator 2 in 3D reminds us what we’ve still to learn about AI and robotics

Brain interpretation

People are astonishingly capable of making sense of language, even though it is often ambiguous. Even a simple sentence of well-formed words has many different interpretations.

For instance “time flies like an arrow” could mean “you should time flies like you would time an arrow”, or “time flies like an arrow would time flies”, among many other options.

You can understand that these are all possible but you probably chose the most common interpretation, “time moves fast in a similar way to an arrow”. How do you do that?

Understanding language is just one example of the amazing feats of computation you are performing at every moment, without even being aware of it.

Another is understanding visual images. Every two-dimensional image on your retina could have been generated by any number of three-dimensional scenes. Each edge could be part of several different objects, or indeed just noise. But you almost always get it right.

One difficult example is segmenting objects from background, even when the images (and thus object borders) are very noisy, and the objects are complex shapes, which is often the case with medical imaging. Even without noise it can be hard for algorithms to segment out what’s important.

Another difficult example is adversarial images, specifically designed to fool computer vision algorithms, even though humans have no problem with them.

Current computer algorithms and programs are catching up with human skill in domains like language understanding and processing visual images.

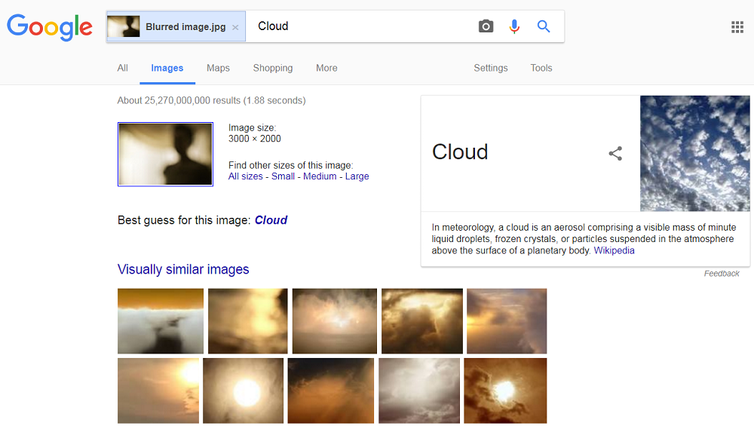

What do you see in this image? Try searching the image on Google and it thinks it’s an image of a cloud (see below).

Flickr/Janaina C Falkiewicz, CC BY

Google image results for the blurred image.

Google/Screenshot

But Google and other tech companies would love to get better at this, to improve both their products and their ability to extract statistical patterns from vast amounts of data.

Tech needs neuroscience

That’s why they have been hiring from the neuroscience sector to gather people with backgrounds in understanding how biological brains perform computations.

For example, earlier this year Uber hired Zoubin Ghahramani, an expert in machine learning and former neuroscientist, as its chief scientist.

Demis Hassabis, founder of the start-up DeepMind (subsequently acquired by Google for more than £400-million) who also has a background in neural processing, recently boasted another recruit from neuroscience.

These are just some of the high-profile cases; there are others who are being hired from PhD and postdoc positions who don’t make headlines. The research in AI at Google is producing results, with a rise in the number of papers published in academic journals.

Biological thinking

Biological brains work nothing like digital computers. Brains are massively parallel, harnessing the power of a huge number of relatively slow and simple processing elements working together. Each neuron is connected to many others so that in the human brain there are about a million billion connections.

Digital computers instead do one thing at a time, albeit extremely fast. Even so-called parallel computers simply split the problem up into smaller chunks, but each chunk still involves performing many individual steps.

Brain-like parallel computation can be simulated on digital computers. Indeed, deep learning is a method for a machine to learn from large amounts of data that was originally inspired by neuroscience, and is now a key ingredient of Google’s algorithms.

But on digital computers this requires large amounts of power, while the human brain uses less power than a light bulb.

Simultaneously, our knowledge of the brain itself is being transformed by new technologies. These include new methods for recording large-scale neural activity at single neuron resolution.

Read more:

We all need to forget, even robots

In humans non-invasive techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) average together the activity of tens of thousands of neurons. But in animal models it is now possible to label neurons with fluorescent markers that glow brighter when neurons are active.

Using new types of microscopy then allows us to see every neuron in a large region, sometimes even the whole brain, working together to solve problems.

New neuroscience techniques such as these are poised to revolutionise our understanding of how biological brains perform their astonishing feats of computation.

These new insights will then help drive new innovations in the algorithms that power technology companies, by revealing the computational tricks that biology uses to stay competitive.

Algorithms are gradually allowing computers to think more and more like a human. But as AlphaGo recently demonstrated, predictions of how long it will take for computers to achieve human (or superhuman) level performance on any particular task are often wrong.

So how long before a Google search will be able to understand the phrase at the opening of this article? Let me just finish by saying (and check for yourself how Google fails on this one as well):

Wlme t th ftre

Geoff Goodhill receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council.