Why women’s voices are missing from the future of work debate

Shutterstock/PrazizImages

The business of prophesying the future of work has a gender problem. Admittedly, some of the scenarios around automation predict gains when it comes to workplace equality. But until the people shaping the debate are more representative of wider society, these visions are presenting a skewed version of the future of work.

The debate about the future of work focuses largely on the impact of automation. Media firms, management consultancies, NGOs, business schools and economic modellers are all envisaging a new version of capitalism.

This has led to an abundance of studies and reports, based largely on hypotheticals predicting job losses, which have fuelled “automation anxieties” around the prospect of a jobless future. What initially appeared as science fiction scenarios quickly became absorbed in mainstream thinking, shaping expectations about workplace technologies of the future.

These ideas claim to describe what is coming, yet they only offer a partial view of the future, as they have emerged from reports written in sectors that remain male-dominated and where female voices represent the minority. If contributors were more diverse, we might see more imaginative alternatives concerning the balance of waged work and unpaid work. This could lead to more interesting scenarios in terms of working time, location of work and more equitable recognition of household responsibilities.

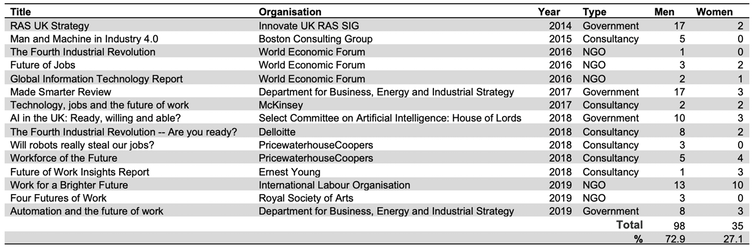

So who are the speculators around automation and whose interests do they serve? The table below gives an overview of some key reports, showing the breakdown by gender. In terms of representation, it shows that authorship is male-dominated in more than 70% of cases. Female representation is particularly concerning among policy makers, with only 17% of authors of government commissioned reports being female.

The male-dominated world of policy reports.

Author provided

Management consultancies

Management consultancies are at the forefront of the future of work debate, publishing some of the most highly cited and influential reports.

According to KPMG, one of the “big four” accounting and consultancy organisations, potential changes in the future of work represent big business (their prediction values this market at £3.4 trillion), helping understand why so many key players want a piece of the pie.

This has lead to a great deal of speculation on the numbers of job losses arising from automation which can be used in an attempt to sell their solutions to interested parties. Deloitte predict a fall in 35% of UK jobs, KPMG predicts 7%, while PwC estimates it is less than 30%. However, while their outcomes differ, the people behind the figures are less diverse.

Both gender and race inequalities remain pervasive within these firms, particularly among more senior roles. There is limited inclusion of women on the panels, boards and working groups that produce these reports (less than half of the authors of reports from the big four accounting and management consultancies were women, as seen in the table above).

For example, the highly cited report on the Fourth Industrial Revolution was authored by 10 experts at Deloitte, two of which were women. Similarly, Boston Consulting’s Man and Machine in Industry 4.0 included the expertise of five men and zero women – an appropriate title for a seemingly male-centric report.

Economics

Academics, particularly from economics, have contributed to some of the most highly cited articles proclaiming the end of work as we know it. Research from 2017 estimated that 47% of US jobs will be automated in the next decade or two, for instance.

But if we look at the gender balance in economics as a subject area, we see that this represents a male-dominated view of economic futures. The graduate pool of female economists is half the size of that of male economists. The future looks even more bleak when you factor in PhD economics programmes: approximately 70% of students are men – unchanged since the early 1990s. This means that those shaping the debate are not representative of the wider population.

Government

These works also serve as important resources for informing state policies and industrial strategy. The UK government has a poor track record when it comes to being at the cutting edge of robotics and AI, falling behind many G7 countries. Its gender practices are similarly archaic. Take the first industrial strategy for robotics and autonomous systems from 2014, which was published by a 19-member steering committee that included only two women.

Similarly, the House of Lords select committee for artificial intelligence has just three women in its 13-member group. Meanwhile, the industry-led Made Smarter Review, commissioned by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, called upon the expertise of 20 industry leaders – only three of which were female.

Tech sector

The technology sector is notorious for inequalities and the “Brotopia” bubble is far from bursting in Silicon Valley. This is problematic, not only because of the industry-wide marginalisation of minorities, but because technologies embody the values of their makers in their design.

In the case of Wikipedia, the overwhelming majority of contributors are male and the content available reflects their interests. For example, the pages listed for female poets have been edited 600 times, compared with the more detailed classification of female porn stars, where the edits is closer to 2,500.

If technology developers merely reflect the desires and perspectives of the “male, pale and stale” stereotype, then new technologies are unlikely to accommodate the diverse social contexts within which they operate.

But in all these examples, while redressing unequal representation is a step in the right direction, it is not intended as a cure all. Broader social change is needed to address the structural inequalities embedded within the current organisation of work and employment, since this serves as the foundation for the future.

Without a diverse range of critical minds and voices contributing towards the debate, society is left with a somewhat distorted picture of future options. The lack of alternatives which is being presented is likely to lead to self-fulfilling, one-track prophesies, augmenting existing inequalities.

Debra Howcroft receives funding from ESRC.

Abbie Winton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.